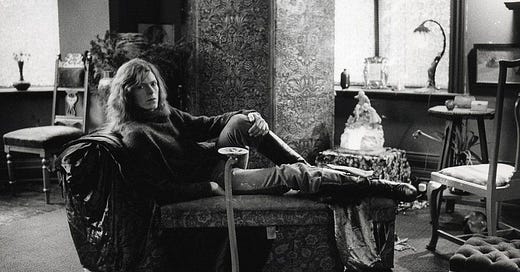

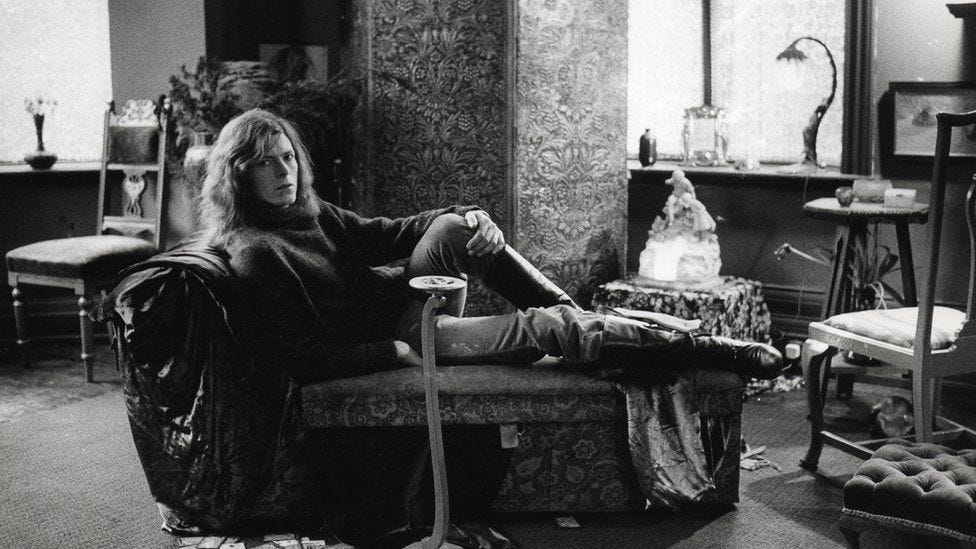

David Bowie, 1970

“When a man stops believing in God, he doesn't then believe in nothing, he believes in anything.”

G K Chesterton

WE have reached the 1970s and David Bowie is having an erotic encounter with God. Or maybe Satan.

His nebulous body swayed above

His tongue swollen with devil's love

The snake and I, a venom high

I said "Do it again, do it again"

It is not obvious that this is a good idea. Voices exhort him repeatedly to “turn around, go back”. But he cannot resist.

Breathe, breathe, breathe deeply

And I was seething, breathing deeply

Spitting sentry, horned and tailed

Waiting for you

This is a new decade, one that would help define Bowie and one that Bowie would help define. But neither party would know this for a few years yet. His creativity and spirituality were built for now on the same shifting sands, and these were times of murk and strangeness and surprises.

The first song on his first album of the 1970s is called The Width of a Circle; the above quotations and the title of this piece are taken from it. It is a new thing and an old thing. It sounds musically like nothing he had done before (and like nothing he has done since). But we could see these lyrics coming.

We have seen how the traditional Anglicanism of his childhood offered comfort but ultimate dissatisfaction. We have seen how the Buddhist foray of his teenage years brought inspiration and insight but demanded a commitment he was unwilling to make. We have seen how he felt launched, driven, propelled by forces he did not control and that this was thrilling but unsettling. A tempestuous dalliance with some mighty supernatural entity is the least we could expect. (Even the name of the song shows more continuity than change: the illustration on the back of his last album of the 1960s is titled Width of a Circle.)

What we cannot know is how seriously to take the song. The garish spiritual imagery sounds on a casual listen to be no more revealing than that employed to the point of cliche by the likes of Black Sabbath or Deep Purple, whose sounds the song evidently strives to emulate. There may be no depth to it at all.

Yet Bowie said of the song a year later: “I went to the depths of myself in that.”

Uncertainty, vagueness, flashes, dabblings, sparks. David Bowie is already four years and three albums into his career but all is still nascent. There have been buds aplenty yet only one real bloom, and perhaps that was only a plastic thing anyway, a novelty cash-in born of circumstances never to be repeated.

But what makes this phase frustrating is what makes it fascinating. The artistic palette was replete with colours, but too many, and the technique remained immature. In other words: anything could happen.

We have looked so far only at the second part of the song. The first might be more significant, because it tells us that Bowie was getting quite heavily into the works of Friedrich Nietzsche. Bowie sings:

I ran across a monster who was sleeping by a tree

And I looked and frowned and the monster was me

As Nicholas Pegg points out1, there are vivid echoes here of Also Sprach Zarathustra and Jenseits von Gut und Böse. The ideas of Nietzsche would go on to inform much of Bowie’s work over the ensuing decades.

Nietzsche is perhaps the most famous atheist in all philosophy, so his presence may seem odd in a project with God in its title. But anyone who takes religion seriously should take Nietzsche seriously, because he took religion seriously. It was his profound understanding of religion that gave much of his work its exhilarating force. Here is the writer and theologian Peter Rollins reciting one of Nietzsche’s most influential passages:

Nietzsche understood that a dead God entailed a shattering of the world as we knew it. The time of simple truths had passed. Moral absolutes could not hold. Such ideas were irresistible to Bowie and his pathological curiosity about the nature of things. (We will revisit Nietzsche at a much later moment of spiritual confusion in Bowie’s life, when the question of the presence or absence of God would take on a new significance.)

There is a lot in this song. Elsewhere, Bowie sings:

We asked a simple black bird, who was happy as can be

And he laughed insane and quipped "KAHLIL GIBRAN"

Gibran was another spiritual guru of sorts. He was a Lebanese-American best known for writing The Prophet, which formed part of the countercultural canon and was influenced by his own Maronite Christianity as well as the Bahá’í faith, Islam and Sufi mysticism. A spiritual polyglot for a spiritual polyglot.

The song is on an album called The Man Who Sold The World. Later we encounter for the first time another figure whose influence would endure.

He is there on a song named After All:

Live till your rebirth

And do what you will

We are familiar with the idea of rebirth, it being a tenet of the Buddhism that had fascinated Bowie. But “do what you will” comes from a different source. It is the guiding principle of Thelema, an occult religious movement founded by a man named Aleister Crowley. Lurid tales of black magic and ritualistic sex surrounded him; by the 1920s his infamy was such that the press declared him “the wickedest man in the world”. The spiritual devastation wrought by what Bowie later called “Crowleyism” would become apparent in the following years, and we will examine this in due course; but for now, Crowley remained a man of intrigue for the young artist.

This continued into his next album, Hunky Dory, which was released in 1971. His talents as a songwriter were now crystallising; the record has two of his best known songs, Changes and Life on Mars?, and it is often rated among his finest LPs. But beneath the crisper song constructions, carefully honed melodies and intricate arrangements lurked familiar turmoil. Psychic terror has never worn a prettier mask.

This is made most explicit on a song named Quicksand, which sums up everything about this time of Bowie’s spiritual questing. It begins:

I'm closer to the Golden Dawn

Immersed in Crowley's uniform

Of imagery

The Golden Dawn was an occultist magical order whose popularity peaked in the 1890s; Crowley was a member. Bowie sings of being “torn between the light and dark”. While he was “a mortal with potential of a Superman” (Nietzsche envisaged an “Ubermensch” who would transcend conventional human morality), he nevertheless remains “tethered to the logic of Homo Sapien”:

Can't take my eyes from the great salvation

Of bullshit faith

As he approaches the song’s sublime chorus, he sings resignedly:

I'm sinking in the quicksand of my thought

And I ain't got the power anymore

And then, to a melody that may be as beautiful as any he wrote:

Don't believe in yourself, don't deceive with belief

Knowledge comes with death's release

Aah-aah, aah-aah, aah-aah, aah-aah

And so this dense and wordy song dissolves into wordlessness. The intellect can do only so much. There comes a point where one must let go.

Bowie would soon be gripped by a new sense of mission. There would be a hitherto unknown sharpness, direction and urgency; the result would be his transformation into an extraordinary kind of star. It may well have looked like he had finally escaped the quicksand.

A funny thing about sand, though: it’s hard to shake off.

If you enjoyed reading this, do feel free to share it by clicking below. Thank you.

Next on Bowie/God:

David Bowie, Ziggy Stardust and the Messiah

Nicholas Pegg, The Complete David Bowie, Titan Books, 2016, p312-313