No confession, no religion

David Bowie transforms into a shiny superstar. But lurking in the shadows are familiar fears and desperate hopes

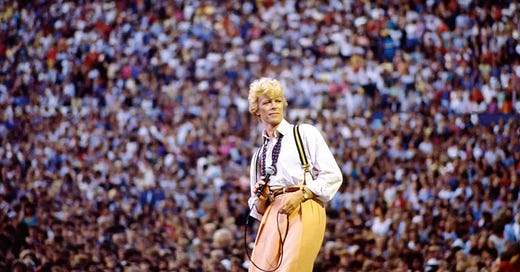

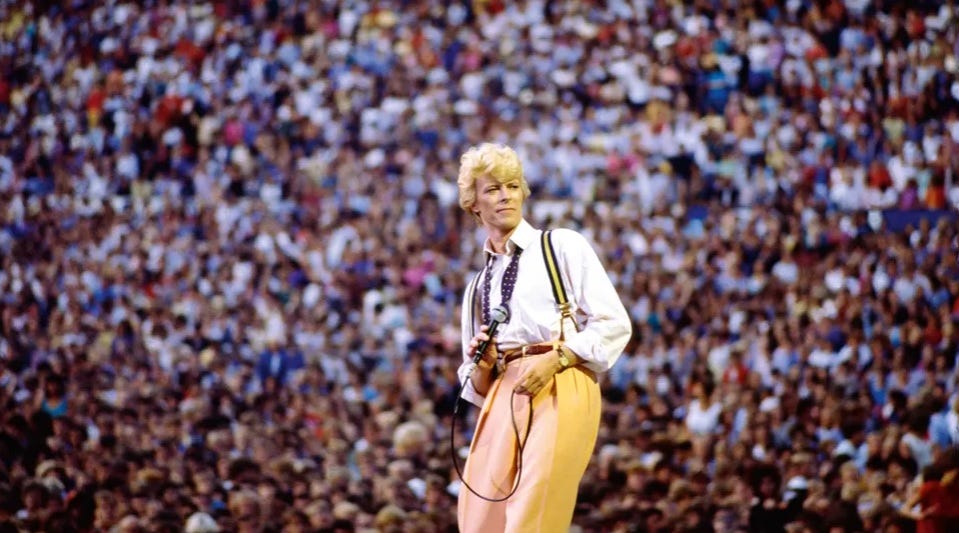

David Bowie performing in Edmonton, Canada on the Serious Moonlight tour in 1983 (picture: Denis O’Regan)

Things don’t really change.

David Bowie seemed like a new creation in 1983. There was once a David Bowie who was jittery and intense, whose natural constituency was populated by outsiders and misfits, whose art was daring, who lived on the outskirts, who personified the zeitgeist and signalled to the future. Now there was a David Bowie whose tanned and healthy features were crowned with a blond bouffant, who wanted to entertain the mainstream, whose music filled charts and airwaves and stadiums around the world, who no longer threatened anyone or anything. From a certain perspective, it looked like he had gained the world and lost his soul.

But things don’t really change.

Bowie had gone three years without releasing an album. Yet he had gone nowhere. Since Scary Monsters (and Super Creeps) came out in 1980, he had played the title role in The Elephant Man on Broadway and the title role in the BBC’s production of the Bertolt Brecht play Baal, for which he also recorded an album, and he shot major roles in the films The Hunger and Merry Christmas, Mr. Lawrence. He had also had a number one single, Under Pressure, which he recorded with Queen.

Still, the sound was different, and the look was different, and the aura was different. And the difference was different. Low had been different from Station to Station; Young Americans had been different from Diamond Dogs. The Thin White Duke had been different from Ziggy Stardust. But now the difference was in the direction of sameness, in the direction of conformity, in the direction of the familiar. Difference had meant risk; now it meant safety.

Bowie had made some compromises with commercial reality in the 1970s. His record company thought the Ziggy Stardust album lacked a hit single, so he wrote Starman. The sound of Station to Station was softened to broaden its appeal. His genius however lay in his ability to draw his audience in whatever direction he wanted to take them. Now he specifically wanted to record chart hits. He had abjured his role as leader, and was now a follower; and the audience he was following was no longer really his.

But things don’t really change.

The album he released in 1983 was called Let’s Dance. Its personnel were entirely new. Its producer was Nile Rodgers, who had produced and played on disco smash after disco smash. Its cover had Bowie as a boxer, topless and toned; this was a man who had been pictured on previous albums wearing a dress and resembling an alien, a man who had sung of being “not much cop at punching other people’s dads”.

It opens in perky fashion, but this is not the perkiness of youth. The energy and enthusiasm here are those of a sensible man in his 30s. His first words are not sung, but said, in an almost offhand manner, and advertise his maturity:

I know when to go out

And I know when to stay in, get things done

Then, with the utmost commitment, the singing begins:

I catch a paper boy

But things don't really change

I'm standing in the wind

But I never wave bye-bye

But I try, I try

The song is called Modern Love and it sounds completely different from anything he had ever recorded. It is unreservedly, unironically upbeat; it is bright and bold and brisk and bouncy. There is no mystery here, no strangeness, no danger; just a catchy, radio-friendly song, the catchiest, radio-friendliest thing he had made. And the words of the singalong call-and-response chorus, shared with some smiley backing singers, go:

Never gonna fall for

(Modern love)

walks beside me

(Modern love) walks on by

(Modern love) gets me to the church on time

(Church on time) terrifies me

(Church on time) makes me party

(Church on time) puts my trust in God and man

(God and man) no confession

(God and man) no religion

(God and man) don't believe in modern love

So this apparently lightweight and undemanding number turns out to be a heartfelt rumination on the relationship between mankind and the divine, and the oppressive character of organised religion.

Modern Love is a simple and straightforward description of beliefs that Bowie would later explore in more depth. It tells of a faith liberated from human institutions and their dogmas and their pettiness and their cruelty. The church here is not somewhere one encounters God, but rather a place one merely attends, dutifully and doggedly; there is a terror in that, a terror to which the only appropriate response is ecstatic rebellion. Those who pose as intermediaries between God and man talk of sin and shame, but he’s having none of it. God and man. That’s all there is.

If it seems a little absurd to write about song like this in such a way, then that is to Bowie’s great credit. He would have made a great magician; aside from anything else, Modern Love is an ingenious act of misdirection.

Modern Love reached number 2 in the UK charts and was a hit around the world.

The second song on the album is called China Girl. It epitomises the album more than any other track: it sounds glossy and commercial in a way that was new for Bowie, while simultaneously being evidence of a deep continuity. In this case, it is not even a new song masking a familiar theme: the song itself had already been around for six years. It originally appeared on The Idiot, the first solo album recorded by Iggy Pop; it was written with Bowie and produced by Bowie. The version on Let’s Dance is embellished with a generic ‘oriental’ guitar riff and a singalong hook, but is otherwise essentially the same, albeit more smooth and less threatening. What sounds initially like a soft-focus love song reveals itself to be a critique of imperialism:

I stumble into town

Just like a sacred cow

Visions of swastikas in my head

Plans for everyone

It’s in the white of my eyes

The menace turns personal:

My little China girl

You shouldn’t mess with me

I’ll ruin everything you are

By the end, that riff returns, as does that “oh oh oh o-oh, little China girl” hook, and all is disinfected and sanitised and sterilised, and we are back to the daytime radio playlist.

It was another masterpiece of subversion; aided by a video that catered to a range of tastes, it also reached number 2 in the UK charts and was a hit around the world.

The third track brings all of this together. It is a colossal work called Let’s Dance. It may well be the last Bowie song that everyone knows; around the world, it may simply be his best-known song.

It is hard, now, to divorce the song from all that surrounded it and all that followed it and all that it came to symbolise. Let’s Dance heralded a new era for Bowie and arguably for pop music itself; the ensuing tour was an astonishing success, with a show in New Zealand drawing what at the time was the largest crowd by head of population anywhere in the world, and with the likes of Madonna and Prince taking inspiration from it.

But if it was the start of something new, it was also the reemergence of something old.

Nile Rodgers had asked Bowie how he wanted the album to sound; Bowie responded by showing him a photograph of Little Richard, through whom the infant David had fallen in love with rock’n’roll.

Then there was the matter of what Bowie wanted the album to say. And its defining track would refine a theme that had inspired arguably his greatest work.

Let’s Dance originally sounded quite different from the song we know, and was at first called Last Dance. And when the layers of immaculate, shimmering production are stripped away, it reveals itself as a sublime affirmation of love’s power against the forces of oblivion.

After an apparently conventional, untroubled first verse, we hear:

Let's dance

For fear your grace should fall

Let's dance

For fear tonight is all

Let's sway

You could look into my eyes

Let's sway

Under the moonlight, this serious moonlightAnd if you say run

I'll run with you

And if you say hide

We'll hide

Because my love for you

Would break my heart in two

If you should fall into my arms

And tremble like a flower

Like the lovers by the Berlin Wall, here is a couple defying death through an act of passion. As Bowie said in 1983: “Lyrically, the thing has a lot more to do with “Heroes” than it has to do with a disco lyric song. There’s a desperation behind the lyric.”

“Heroes” was not the first time that Bowie had explored the idea of confronting catastrophe by expressing humanity. The song Aladdin Sane, released in 1973 on the album of the same name, is inspired in part by Evelyn Waugh’s novel Vile Bodies. The book ends with young people drinking champagne in a car on a bloody battlefield; in the song, Bowie sings of “battle cries and champagne”, and its subtitle is '1913-1938-197?’, suggesting that calamity is imminent.

A more recent song had also shared this theme. Under Pressure depicts a society placing unbearable strain on its people. The only way to cope is through love:

'Cause love's such an old-fashioned word

And love dares you to care for

The people on the edge of the night

And love dares you to change our way of

Caring about ourselves

It ends:

This is our last dance

This is our last dance

This is ourselves

This appears by now to have become one of Bowie’s core beliefs. It is by nature metaphysical. It would be crass to claim it for a particular religion, but it has a strong tradition at least in Judaism and Christianity: the Song of Songs asserts that “love is strong as death, passion fierce as the grave”; the First Epistle of John says “there is no fear in love, but perfect love casts out fear”. And that is aside from the exploration of such ideas by the Christian theologian Paul Tillich.

The steps of the last dance, echoing through eternity.

Unusually for a Bowie album, Let’s Dance is really all about the singles. The rest of the record is somewhat anticlimactic. The fifth track, Ricochet, deals with societal oppression and at times employs a spiritual vocabulary (“turn the holy pictures so they face the wall”; “sound of the devil breaking parole”), but it all seems rather forced, so it may be unwise to regard it as spiritually revealing. Other than that, there’s a cover, a rerecording of a song from the previous year and a couple of new songs that can be described at best as lightweight.

The album therefore makes for a curious listen. But it achieved something extraordinary: it got people around the world dancing to songs about the relationship between God and humanity, the dead hand of organised religion, the horrors of imperialism and a wild claim that the end of being can be overcome by love.

A much later song, perhaps his most significant single after this time, would make the same claim, in very different circumstances, in a very different voice. But that is to come.

Because things don’t really change.

If you enjoyed reading this, I would be grateful if you would please share it with others. Thank you.

Next on Bowie/God:

David Bowie gives up believing the strangest things, and pays the price