What in the world can I do

Bowie abjures mysticism as he remakes himself. But has he found something greater?

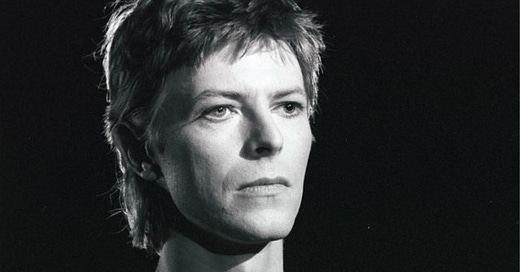

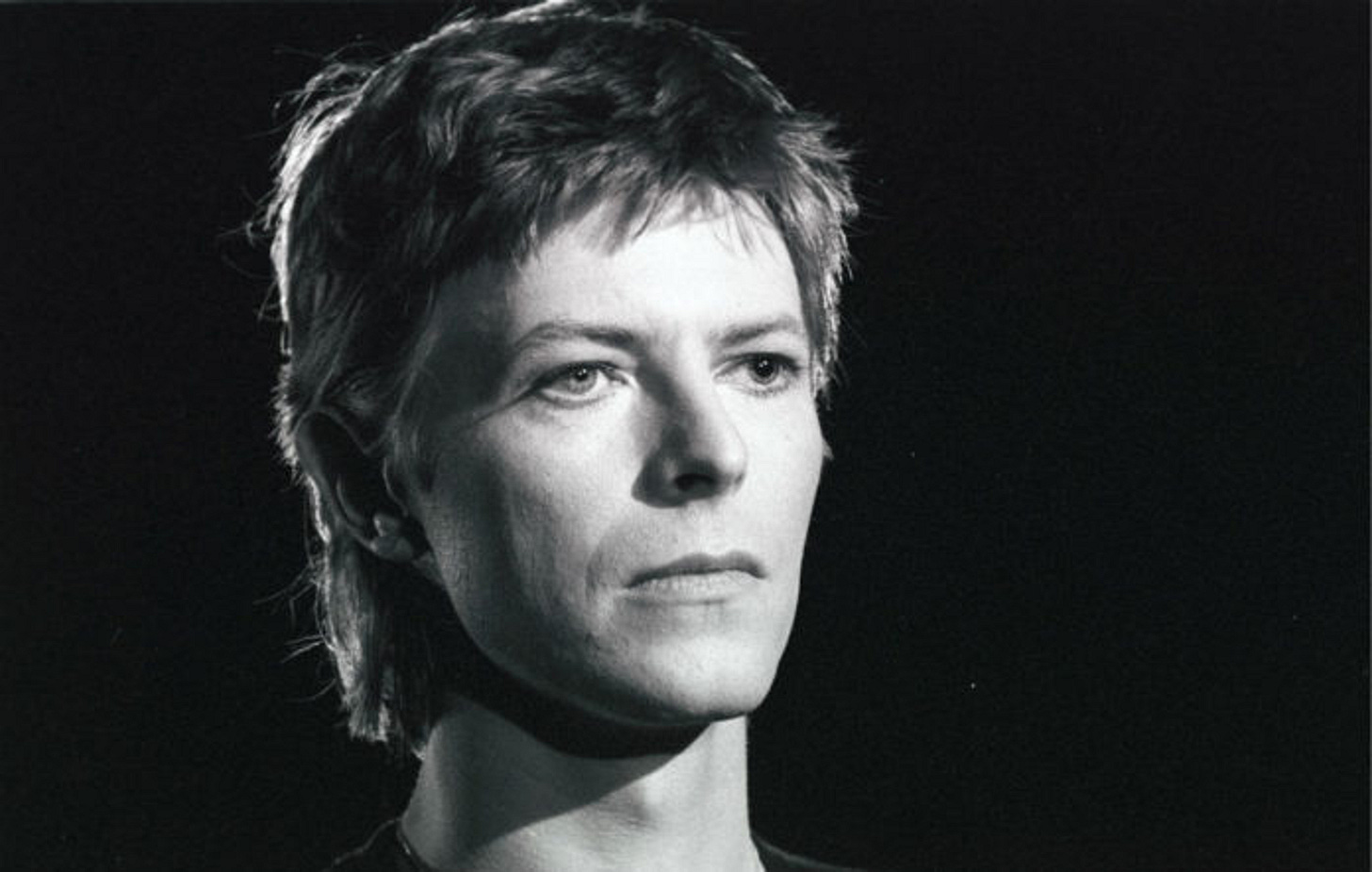

David Bowie in 1977

HARTY: Do you indulge in any form of worship?

BOWIE: Er…Life. I love life very much indeed.

Interview with Russell Harty, 1973

One of the few very badly attempted suicide attempts that I tried…that night everything kind of came to some kind of spiritual impasse. And I really was down in a hotel garage…I started going round and round, faster and faster. And let go.

And as I let go I ran out of petrol. I just slowly came to a stop. I thought, ‘this is the story of my life’.

David Bowie, 1999

It is tempting sometimes to see the career of David Bowie as a set of distinct phases, with distinct looks and sounds and patterns of behaviour. It is often depicted as a series of hairpin bends, of swerves and skids and handbrake turns, the lights always either red or green, never amber.

The shift from the terror and tumult of Los Angeles to what is typically called the ‘Berlin period’ seems a change as sudden and dramatic as any. The paranoid and cocaine-fuelled existence in an LA mansion was replaced by a flatshare in a modest quarter of a modest city. The fantastical, freakish and theatrical outfits were replaced with flat caps and dad shirts. The swaggering bluesy riffs and rousing choruses were replaced with textures and shapes hitherto unexplored by a mainstream artist. He stopped living like a rock star; he stopped looking like a rock star; he stopped sounding like a rock star.

Yet the lines were not as clinical as they are made to look. Bowie may have left the scene of his darkest spiritual terrors, but he still took a lot of baggage with him. His move to Europe in the middle of 1976 was a matter of survival. It was an attempt at a clean break; but it was rather less neat and tidy than that phrase suggests.

A degree of spiritual anguish remained. As did the cocaine addiction. The suicide attempt in the car park followed a distressing incident earlier that day. As Bowie recalled in 1999:

The full story is rather alarming. It involved a coke dealer whose car I saw on the Kurfürstendamm in Berlin one day. And I’d gotten it into my mind that he’d screwed me over a deal. My very good friends Iggy Pop and Coco Schwab had clubbed together and bought me a really cheap but apparently lovely Mercedes. I was so crazed I started ramming him in the Kurfürstendamm. In daylight, 12 o’clock in the day. And I rammed him and I rammed him and I could see he was absolutely mortally terrified for his life. I’m not surprised. I rammed him for a good five to ten minutes. Nobody stopped me. Nobody did anything. And I got out of it and thought ‘what am I doing?’.

The change in the music was more of a transition than a transformation, too. The first album Bowie made in his new environs was called The Idiot. It was nominally by Iggy Pop, but Bowie produced it and co-wrote all the songs; the impression often given is that Bowie was essentially directing the project, with Pop providing the lyrics and vocals. It sounds like a blend of Bowie’s immediate past and immediate future: there is the icy abrasiveness of his previous tour, and the clipped claustrophobia of his following album.

The Idiot was not recorded in Berlin. Neither was most of Low, which was to be Bowie’s next record. Both were recorded at a chateau near Paris. Part of the fabric of Low was inspired by German music Bowie had admired for years; he had begun to incorporate it on Station to Station and its accompanying tour. He retained the rhythm section from Station to Station: Carlos Alomar on rhythm guitar, George Murray on bass guitar and Dennis Davis on drums. The producer was Tony Visconti, with whom Bowie had first worked in 1967. His new collaborator was Brian Eno; he had been a founding member of Roxy Music, who emerged into public consciousness around the same time as Bowie in 1972 and occupied the same ‘high’ end of glam rock. Bowie had also long been enamoured of Eno’s solo work, especially in the genre he essentially invented: ambient music. So this fresh venture had deep roots.

But the result would be so startlingly different from what had come before that we will need to write about it in a new way.

David Bowie has made it easy for us so far. His spiritual paths and fascinations have often been made explicit in his lyrics. When he was particularly interested in Buddhism, he wrote about Buddhism; when he was particularly interested in occultism, he wrote about occultism; when he was particularly interested in Kabbalah, he wrote about Kabbalah. And so on. Sometimes references to spirituality and specific traditions and practices would be more oblique, but it has not been a struggle to find them.

The most immediate and striking change with Low is the lack of words. The album has 11 songs, but only five have what we might call lyrics. And even then, they tend to be sparse and clipped; we have travelled far from Station to Station. There is no mention of any god, or any devil, or any demons, or any messiahs, or any churches or temples or prophets or mystics. And yet a case can be made that Low, and its successor, “Heroes”, are as profoundly spiritual as any works of Bowie’s career.

We can infer what we can from what lyrics there are on Low. Of the five tracks most closely resembling conventional songs, four are concerned with enclosed spaces. The first words we hear Bowie sing are:

Lately I’ve been

Breaking glass in your room again

ListenDon’t look at the carpet

I drew something awful on it

See

(We could speculate that the ‘something awful’ might be the thing he had been drawing on floors for the past few years; if so, this would be this album’s only overt reference to his previous ways.)

The following track tells of another seclusion:

So deep in your room

You never leave your room

Then we arrive at the album’s most famous song:

Blue, blue, electric blue

That's the colour of my room

Where I will live

Blue, blue

Pale blinds drawn all day

Nothing to read, nothing to say

Blue, blue

Next we have the song that was inspired by the suicide attempt. No room this time, but an even tighter space:

Jasmine, I saw you peeping

As I pushed my foot down to the floor

I was going round and round the hotel garage

Must have been touching close to 94

Oh, but I'm always crashing

In the same car

The final decipherable lyric on the album speaks of escape but offers none:

Sometimes you get so lonely

Sometimes you get nowhere

I've lived all over the world

I've left every place

And that’s it. Much of this is sung without Bowie’s usual conviction or passion; some of it is hardly sung at all. It’s one thing for an artist to sound nothing like they did a few years earlier in their career: here, Bowie manages to sound nothing like he did on the album he’d just done.

Perhaps more so than any other of his LPs, Low is a record of two sides. The first is those five brief songs, bookended by two pacy and driving instrumentals. The second is an even greater departure: four slow and solemn and apparently wordless tracks that seem to represent a wholly other form of art. They could be seen to show a way of exiting those rooms, those tight spaces, and opening oneself to a deeper kind of truth.

Eight dolorous monotones spread over 24 seconds introduce Warszawa, the first of these tracks. The texture thickens; it is hard to identify individual sounds, which are all played by Eno, on a piano and three electronic instruments. Themes rise, fall, rise again, rest, rise again, as if gaining strength, acquiring a slow, graceful momentum. Then, they turn; and after four minutes, there is a human voice. And then more: most provide added texture and depths with their long hums and voiced breaths. Over these, a vocal line soon rises, singing mysterious and unintelligible words. These are sung by Bowie, but his voice is soon manipulated to sound like a choirboy. Then those earlier themes return. The piece ends almost resignedly.

Here is a strange confusion. Bowie said the piece is “about Warsaw and the very bleak atmosphere I got from that city”. But the great Bowie writer Chris O’Leary, whose research is typically impeccable, says that Bowie named the track “well after he and Eno had made it”. So the place did not inspire the piece; rather, the piece put Bowie in mind of the place.

Either way, what is perhaps most striking about Warszawa after repeated listens is the sense of humanity bursting through the subdued stateliness. The instruments, mostly inorganic, play with great deliberation. But the voices surprise, the words never before heard, soaring and swooping in unusual scales, conveying urgency and a kind of desperation. Even though the piece ends quite as it began, it sounds different. The voice changes everything.

Eno spoke about this phenomenon earlier this year, when talking about the role of vocals on his new album:

I’m a landscape painter in terms of music, I suppose. But this time I wanted to have somebody in the landscape. Putting a human in the picture makes it a quite different kind of picture. I’ve seen this myself. If you look at a landscape painting, and there’s nobody in it, you look at it in a certain way. If you put even the tiniest figure in there, even down in one little corner, a single human figure, your eyes move in an entirely different way. You keep returning to that figure, because what you’re then looking at is a human in relation to the world you have created…this person is sort of showing you ‘here’s the world, and here’s how I feel about it, here’s how I behave within it’.

We hear in Warszawa the sound of the human spirit beautifying the world it inhabits and defying the forces that would oppress it. There is a transcendence; it is as if Bowie is singing in tongues.

This core belief in what we might call the soul - not only that it exists but that it is a source of transformative power - finds its place at the heart of Bowie’s work during this period. It is his fundamental statement.

The idea illuminates Bowie’s musical choices around this time. Years later, he contrasted his approach with that of the German band Kraftwerk:

Much has been made of Kraftwerk’s influence on our Berlin albums. Most of it lazy analyses I believe. Kraftwerk’s approach to music had in itself little place in my scheme. Theirs was a controlled, robotic, extremely measured series of compositions, almost a parody of minimalism. One had the feeling that Florian and Ralf were completely in charge of their environment, and that their compositions were well prepared and honed before entering the studio. My work tended to expressionist mood pieces, the protagonist (myself) abandoning himself to the 'zeitgeist' (a popular word at the time), with little or no control over his life. The music was spontaneous for the most part and created in the studio.

In substance too, we were poles apart. Kraftwerk’s percussion sound was produced electronically, rigid in tempo, unmoving. Ours was the mangled treatment of a powerfully emotive drummer, Dennis Davis. The tempo not only 'moved' but also was expressed in more than 'human' fashion. Kraftwerk supported that unyielding machine-like beat with all synthetic sound generating sources. We used an R&B band. Since 'Station To Station' the hybridization of R&B and electronics had been a goal of mine.

This is an expression of spirituality quite different from those hitherto explored by this project. It is less concerned with particular practices or traditions, like Buddhism or Kabbalah: it is more an expression of fundamental belief, or at least hope. But it has a place within conventional religions, and perhaps found its most influential advocate in the form of Paul Tillich, a German-American philosopher and one of the leading Christian theologians of the 20th century.

One of the books written by Tillich is called The Courage to Be. It was published in 1952 and was remarkably popular for a work of its kind. It is a profound affirmation of what might be called ‘being in spite of nonbeing’. For Tillich, courage is “self-affirmation in spite of anxiety over the threat of nonbeing”. There are vast forces that threaten existence: Tillich calls them “fate and death,” “guilt and condemnation,” and “meaninglessness and emptiness”. Affirming being in spite of all these threats is an act of supreme courage. And the ultimate source of the courage to be is what Tillich calls the “God above God”: the God that is beyond our limited understanding, the God that transcends conventional theism, the God that is not somewhere in the distance, but is the very ground of being itself.

This last point overlaps intriguingly with Gnosticism, another mystical tradition with which Bowie had a fascination. He said in 1996, when talking about his spiritual questing:

There’s a term that the Gnostics use, which is called the God beyond God. There’s a sense that one’s trying to find some merit in the chaos that we perceive as our existence…the idea the early Gnostics had that there is in fact the deep, the depth, of the God beyond God, that there’s something beyond that that one can’t call a singular entity but something that just pervades everything - I think that's one of the major searches that I’ve probably made in my life.

There are three more pieces on Low. Two of these feature Bowie’s voice; on one, he sings again. It is the last track on the album and is called Subterraneans. Bowie said it was about “the people that got caught in East Berlin after the separation – hence the faint jazz saxophones representing the memory of what it was”. His voice begins in mournful breaths, before he sings some words, initially with a kind of serene melancholy, before building into something more impassioned and perhaps anguished. In contrast to Warszawa, the words sound like they may be English; but there is no consensus regarding what they are, and they remain impenetrable. The most that can be said is that they twice mention a failing (or fading) star. To claim this is in any way a joyful or even hopeful piece would be absurd; but the focus here again is on the human. Here, the forces of nonbeing are a totalitarian regime that has drained colour from life. Yet the life remains, and the saxophones play on in the memory. Somehow, in spite of everything, there is still beauty; and Subterraneans is beautiful.

There is another word connected to these two tracks. Bowie asked Eno to begin work on a piece with a “very emotive, almost religious feel to it”. That piece became Warszawa. A man working for RCA, which was Bowie’s record label at the time, described another track as “religious”. That piece was Subterraneans.

Yet neither makes any mention of God. Funny thing, religion.

David Bowie’s next album was called “Heroes”. The quotation marks are deliberate.

“Heroes” was released just a few months after Low and is something of a companion piece. Visconti returned, and Eno returned, as did the rest of the band apart from guitarist Ricky Gardiner; he was replaced with Robert Fripp. “Heroes” was recorded entirely in Berlin, at Hansa Tonstudio, where Low had been completed.

The album sounds more expansive, clear and reverberant than Low. But a number of the same working practices were employed in an attempt to foster creativity and avoid cliché: spontaneity and randomness were part of the process. The albums also share a general pattern: things that sound like conventional songs on side one, more abstract and instrumental tracks on side two.

Two of these pieces have a distinct sense of place. The first is called Moss Garden. We are suddenly far from the intensity and peril of Berlin; we are in a Zen Buddhist temple in the city of Kyoto in Japan. It is a place of sublime serenity. The principal sound is that of a koto, a traditional Japanese stringed instrument.

Bowie would use the koto again, in 1999. At the time, he said:

The koto I’ve used a couple of times…when I get to write a piece of music that for me is sort of maybe expressing a spiritual life, I tend toward the East, because when I was a kid, the things that fascinated me in terms of spiritual adventures and all that tended to be more Buddhistic in nature - they didn’t have much to do with Western religion or Christianity. And so I think I naturally gravitate towards and Eastern form of music when I’m trying to paint a picture of a spiritual existence. That would explain why, often, my instrumental music tends towards the East.

The second is called Neuköln. It is named after a district of Berlin associated again with a dislocated people: in this case, immigrants from Turkey. The piece expresses its spirit not with Bowie’s voice but with his breath: his saxophone is the only recognisably human element in an oppressively inhuman landscape. Bowie grunts and wails and howls and screeches his way through the piece; it is a performance of remarkable expression. It outlives its surroundings, the apparent cause of this anguish, crying out at the end alone; whether this a tale of survival or defeat is open to question.

But elsewhere on the album is a song that leaves no doubt as to the victor. The duration of this victory is irrelevant: it could be one day, it could be forever. It transcends the temporal, for its truth is eternal. The song, like the album, is called “Heroes”.

The song has acquired a remarkable life since it was recorded 35 years ago. It was not a hit when first released; it was perhaps not until Bowie’s performance at Live Aid in 1985 that it became what it has become. When snipped into clips on television screens, it can come across as generic stadium rock bluster, something akin to We Are the Champions by Queen. But it is actually quite different: it is a small, intimate song, made majestic less by the seemingly unstoppable force of the band than by its theme and Bowie’s total commitment to it. An acoustic version might be just as potent.

It is a song of subversion and irony; remember those deliberate quotation marks. Two bruised and broken and unheroic humans will be transfigured. This will be done in spite of the forces trying to destroy them; this is how the forces will be overcome:

I, I will be king

And you, you will be queen

Though nothing will drive them away

We can beat them, just for one day

We can be heroes, just for one day

The material truth is revealed in the second verse:

And you, you can be mean

And I, I'll drink all the time

The scene is one of shame and degradation. In later performances, this is where Bowie began the song; the band would begin casually too.

'Cause we're lovers, and that is a fact

Yes we're lovers, and that is that

Though nothing will keep us together

We could steal time just for one day

We can be heroes for ever and ever

What d'you say?

The song gives the appearance of building into something mighty. But on the studio version, the band remain notably consistent throughout; they have an irreducible steadfastness, a kind of noble solidity, tireless, relentless. The metamorphosis here is all in Bowie’s voice as he relates a scene from Berlin, the powers of death, of guilt, of meaninglessness confronted and defied in a defining and redefining moment:

I, I can remember

Standing by the wall

And the guns shot above our heads

And we kissed, as though nothing could fall

And the shame was on the other side

Oh we can beat them for ever and ever

Then we can be Heroes just for one day

The forces that would destroy are conquered. Love is stronger than death. This is being in spite of nonbeing. This is the courage to be.

As Tillich wrote on the power of being:

One can become aware of it in the anxiety of fate and death when the traditional symbols, which enable men to stand the vicissitudes of fate and the horror of death, have lost their power. When “providence” has become superstition and “immortality” something imaginary, that which once was the power in these symbols can still be present and create the courage to be in spite of the experience of a chaotic world and finite existence. The Stoic courage returns but not as the faith in universal reason. It returns as the absolute faith which says Yes to being without seeing anything concrete which could conquer the nonbeing in fate and death.

It is this absolute faith that powers and radiates from Bowie’s greatest work. The quest for spiritual truth would be ceaseless but this would lie at its heart, and these albums would be its purest expression.

“If I never made another album it really wouldn't matter now,” Bowie said in the 1990s when reflecting on these works. “They are my DNA.”

But the brilliant adventure did not end here. As we will see, there was a world to explore.

If you enjoyed reading this, I would be grateful if you would please share it by clicking below. Thank you.

Next on Bowie/God:

David Bowie crosses the horizon