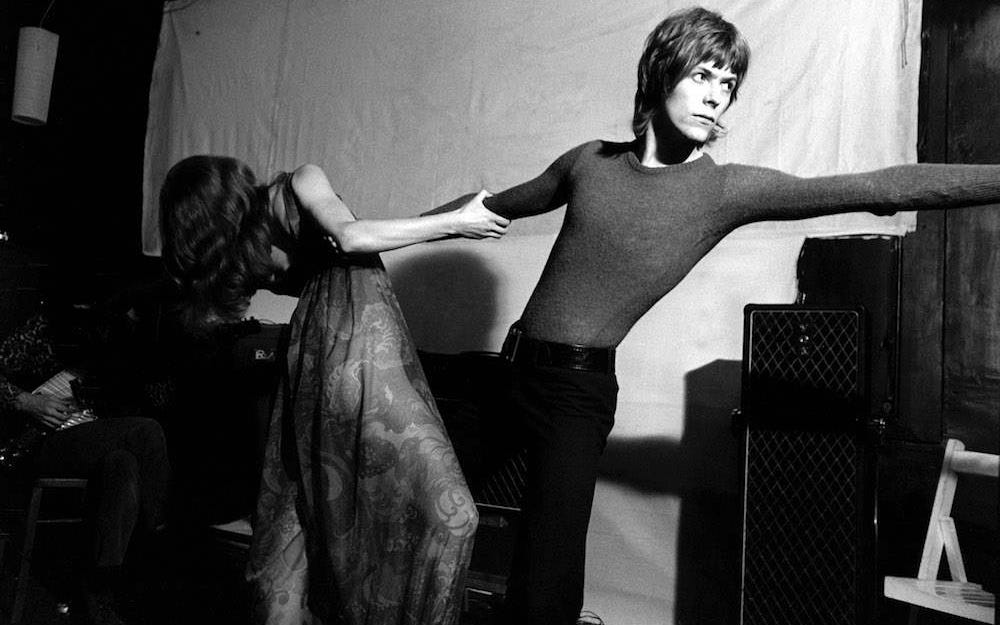

David Bowie with girlfriend and collaborator Hermione Farthingale, 1968

“I was a terribly earnest Buddhist at that time, within a month of becoming a Buddhist monk”

David Bowie

“I was a Buddhist on Tuesday and I was into Nietzsche by Friday”

David Bowie

YOU can see the appeal. The young David Jones had sung in the choir of his local church. He had grown up in a family that was avowedly Church of England. But he also wanted to be cool.

The Church of England was not John Coltrane. The Church of England was not the Rolling Stones. The Church of England was not Carnaby Street or espresso bars or Mod couture. The Church of England was seen to represent much of what teenage rebellion was rebelling against. Alan Bennett’s satire of a vicar in Beyond the Fringe was exquisite.

Some clergy, surveying the seismic cultural shifts of the time, wanted the church to be modernised in turn. There was a movement known as South Bank religion, at the forefront of which was a bishop named John Robinson. He had written a book called Honest to God; it was published in 1963, just before the Beatles’ first LP (the bishop had previously spoken in court against banning D H Lawrence’s novel Lady Chatterley's Lover). Robinson argued it was time for the church to abandon its conventional idea of God, which to him had become outdated and could hold little appeal to what he called “modern man”. His work proved controversial but influential, although that influence appears to be waning now.

Roman Catholicism was undergoing similar tumult. Pope John XXIII led a process of modernisation, having felt the church needed “updating”. Out went the old Latin mass, to be replaced by services in modern languages. Theology and teachings were adapted in an effort to be more relevant to the times.

But David Jones had already seen a glimpse of something different. One his favourite books as a teenager was On the Road, by Jack Kerouac; he also wrote The Dharma Bums. The American had been at the centre of the group of writers known as the Beat Generation, who would enthral Jones with their sense of exotic alien cool and had been influenced strongly by Buddhism.

So hipness was part of the attraction. But the allure went deeper. Buddhism has no place for conventional ideas of God; there is no great authority figure in the sky. To a Buddhist, the self is not a fixed entity; all is in a constant state of change. The dead are neither condemned to an eternal Hell nor exalted to an everlasting Heaven; they can spend time in various realms and be reborn into new bodies on earth. And there is the small matter of an offer of a path to Enlightenment, catnip to the counterculture.

There was a further fascination. David was enthralled by Seven Years in Tibet, Heinrich Harrer’s memoir. It gave an outsider’s eye view of the land before it was invaded by the Communist Chinese People's Liberation Army. It would add a political dimension to David’s deepening absorption. A book called The Lampa Story, written by a man from Devon who claimed his body hosted the spirit of a Tibetan lama, was a another early influence.

Around the time his first album was being recorded, David was living in with one of his former managers in Warwick Square in central London. The British headquarters of the Buddhist Society happened to be only a few minutes’ walk away. David looked in.

He gave an account of the visit in 2001. “Sitting in front of me at the desk was a Tibetan lama. And he looked up and he said: ‘You’re looking for me.’ He had a bad grasp of English, and in fact was saying ‘who are you looking for?’ But I needed him to say ‘you’re looking for me’.”

The lama was called Chime Youngdong Rinpoche; he would become a teacher to David, whose music was being taken to new lands.

BOWIE’S first album is strange and strangely charming; it is hard to think of any other record it resembles. Much of it could be dismissed as lightweight eccentric novelty, and Bowie himself would all but disown it within a couple of years. But one song on it stayed with him, and carries a gravitas and grandeur missing elsewhere. Its name undersells it: it is called Silly Boy Blue.

The album is set mostly in suburbia and nostalgia. Then suddenly, after four short parps of a horn, we are taken to the “mountains of Lhasa". There are “yak butter statues that melt in the sun”. There is a chela (a kind of slave or servant) considering his overself (his ‘true self’). The music, unusually for this album, is elegant, graceful and spacious.

Bowie was far from stardom at this point but was gaining some attention. Silly Boy Blue featured in his first BBC radio session, recorded in December 1967. It would also feature in his second, recorded in May 1968, this time with chants of “Chime Chime Chime” during its instrumental section.

Other songs from the album were immediately dropped from his setlist. Silly Boy Blue would linger for the occasional session, and would have a rebirth of its own in the 21st century: Bowie performed it at a benefit concert Tibet House in New York in 2001, joined by a troupe of Buddhist monks. Bowie recorded an album called Toy in 2000, on which he revisited some of his earliest songs; Silly Boy Blue was the only track from his debut LP to make the cut.

Two other songs from this period are also notable. Karma Man was recorded in 1967 and is an affecting little piece; it was another song Bowie revisited and revised for Toy. We are at a fair or fete: there’s a coconut shy, and families are enjoying ice creams. They are unaware that transcendence lies just yards away. In a “in a tent where no one goes” is “a figure sitting cross-legged on the floor”; “cloaked and clothed in saffron robes, his beads are all he owns”.

The effect on the narrator is striking:

Fairy tale skin depicting scenes from human zoos

Impermanent toys like peace and war,

A gentle face you've seen beforeKarma man tattooed on your side, the wheel of life

I see my times and who I've been,

I only live now and I don't know why

A more frivolous but similarly likeable example is Did You Ever Have a Dream. It was recorded at the end of 1966 and takes as its subject the phenomenon of astral projection, a kind of intentional out-of-body experience. As the song puts it:

It's a very special knowledge that you've got, my friend

You can travel anywhere with anyone you care

It's a very special knowledge that you've got, my friend

You can walk around in New York while you sleep in Penge

Bowie talked about this in 1993:

“I was studying Mahayana Buddhism, which is very deeply involved with astral projection. With his (Rinpoche’s) meditation methods I often felt that I got three or four feet, maybe even further, outside my body and I was absolutely and totally aware of it.”1

A picture is coming into focus. It is of an artistic young man seeking escape from humdrum suburbia and the stuffy and stale religious certainties of the old world. He is enraptured by ways of seeing and being that are so ancient they feel new. These ways are a portal to mysterious places in the world and in the mind. They infuse the art he loves and the artists he idolises. They hold the promise of enlightenment this side of death. They are inspiring his creativity; he writes songs while in states of deep trance2. The image is now clear: the man has found his path.

And yet.

BOAC Flight 506 from New York landed in London late one night in April 1967. On the aeroplane was a 23-year-old from Brooklyn with four guitars and no visa. Among his obsessions were British music and the quest for enlightenment.

No purist, he: his favoured route had been LSD. But while the experience could be beautiful, it could also be horrifying. He knew he had to find another way.

The man was called Tony Visconti. He and his wife Siegrid had become familiar with The Tibetan Book of the Dead via a translation written specifically for LSD trips. The couple kept the transcendental and dumped the pharmacological. Acid was out; Eastern spirituality was in.

Visconti had dreams of making records in London. Within months, they came true. Among the first songs he worked on was Karma Man.

But Visconti appears to have been a little unconvinced by Bowie’s apparent Buddhist turn:

“David and I had Tibetan Buddhism in common, and he talked a lot about meeting and studying with Chime Rinpoche. I was very envious, since it had been a two-year compulsion for me, to meet and study with a genuine Tibetan lama. When I finally met Chime Rinpoche, it was not through David. I got the impression that David was very reluctant to bring us together, and I also got the impression that he exaggerated how much time he'd spent with Chime, although some biographies state that he studied with him for six months.”3

Yet one of Bowie’s girlfriends in the late ‘60s, Mary Finnigan, had few doubts:

"It was a genuine thing. There was no farting about, he was not a butterfly at all."4

Bowie was certainly pursuing Buddhism with zeal in the later months of 1967. He went as far as spending time in a new Buddhist monastery in Scotland, and was apparently on the verge of giving himself over to it. Then a kind of reality intruded.

As he put it:

“I had stayed in their monastery and was going through all their exams, and yet I had this feeling that it wasn't right for me.

“I suddenly realised how close it all was: another month and my head would have been shaved – so I decided that as I wasn’t happy, I would get right away from it all.”

(It ought also to be said that Bowie is not always the most reliable narrator of his own story. Other accounts circulate, claiming that his decision was rather more considered, and was taken after Chime Youngdong Rinpoche advised him to pursue a career in music, as he “wasn’t going to make a great monk”. One of the people who has circulated such an account is David Bowie5.)

But the interest in Tibet was undimmed. The following year, David performed a mime piece called Jetsun and the Eagle, about the invasion by China. By 1970, he said he was no longer a Buddhist, “though a lot of the basic ideas are still with me”.

And so they would remain. Bowie’s impassioned ‘Buddhist phase’ may not have lasted long, but to consider it therefore trivial would be a mistake. As we will see, Bowie’s career is full of enthusiasms that are no less sincere for being short-lived. Think of a gannet, how her dive leaves little impression on the surface of the ocean but takes her deep, how long she is sustained by what she finds.

He would adopt the flying pose first seen in Jetsun and the Eagle in countless tours and videos.

He would release a song in 1997 called Seven Years in Tibet.

He would describe himself as a “mid-art populist and postmodernist Buddhist”.

He would perform at the Tibet House Benefit concerts in 2001, 2002 and 2003.

And he would state in his will that he wanted his ashes scattered “in accordance with the Buddhist rituals”.

So David Bowie may not have given Buddhism his life. But he gave it something that may be just as precious: his death.

“I’ll meet him again in the next life,” said Chime Youngdong Rinpoche.

If you enjoyed reading this, do feel free to share it by clicking below. Thank you.

Next on Bowie/God:

David Bowie is propelled by strange forces beyond his control, over and over again.

References

Kevin Cann, Any Day Now: David Bowie: The London Years 1947-1974, Adelita, 2010, p110

Peter and Leni Gillman, Alias David Bowie, Hodder & Stoughton, 1986, p137

David Buckley, Strange Fascination: David Bowie the Definitive Story, Virgin, 1999

Peter and Leni Gillman, Alias David Bowie, Hodder & Stoughton, 1986, p165

Kevin Cann, Any Day Now: David Bowie: The London Years 1947-1974, Adelita, 2010, p114

Information about Tony Visconti’s arrival in the UK and his spiritual practices comes from: Tony Visconti, Bowie, Bolan and the Brooklyn Boy, HarperCollins, 2007