The hymns of night

A radical shift to the conventional takes Bowie into uncertain times. Time to return to an old certainty

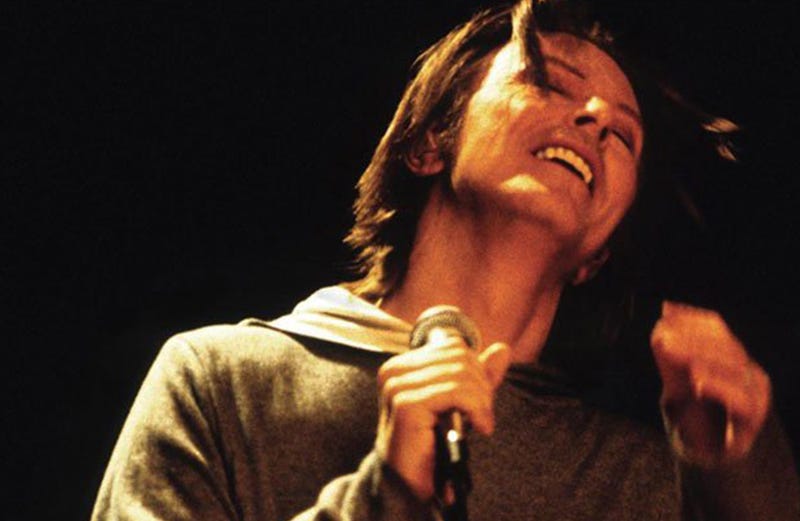

Bowie performing on VH1 Storytellers in 1999

His hair was pin-sharp and radioactively orange. His gown was the sort of thing a Mughal emperor might find a little OTT. The setting was a triumphant concert at Madison Square Garden, where he had just celebrated his 50th birthday by performing a pounding and screeching set with Lou Reed, Sonic Youth, the Foo Fighters, Robert Smith and Frank Black. So when David Bowie said, near the show’s end, “I don’t know where I’m going from here but I promise I won’t bore you,” there was every reason to believe him.

Hmm.

What in fact happened was possibly the single biggest transformation in Bowie’s career. Crazy Rave Uncle was no more: arise, Sporadically Interesting Dad.

Once he had turned 50, the media became more intrigued by Bowie’s money than his music: he had just made tens of millions of dollars by issuing bonds on the stock market. And then the following year was as quiet as any of Bowie’s career, at least in conventional terms: he recorded barely a handful of songs, all of which were one-offs that would forever remain obscure (although two were profoundly significant, for reasons that will become clear in future pieces); he played one gig, at a birthday party for the DJ Howard Stern; his roles in three films were shot, but few would ever watch them.

Yet conventional terms are not always the best way to judge Bowie’s work. He was embarking on a project that would elicit sighs and scepticism but, to some extent, prove prescient. It was called BowieNet and if you were in America you could surf your way to it on Netscape Navigator or Internet Explorer from September 1, 1998, with other countries joining in the ensuing months. Bowie had built much of his career on mystique and distance: now he was extremely available, popping into chatrooms, subjecting himself to matey online Q&As, posting diary entries online, sharing his art and his enthusiasms directly, unmediated.

It is hard these days to convey, perhaps even recall, the sense of excitement that existed around the internet at the time, and Bowie was among its most ardent evangelists. It is also worth mentioning that this excitement was felt far from universally: there was in various quarters a good deal of eye-rolling about it all, similar in some ways to how advocates of cryptocurrencies are (far more deservedly) received today. But to be fair to Bowie, this was not a case of him spotting the next cool thing, commandeering it and proclaiming himself some sort of pioneer: he had used email as early as 1983, and he had ruminated on the ‘World Wide Internet’ while recording 1. Outside in 1994. His interest was true, deep and informed.

And in a curious way, it helps us piece together what we might see as his belief system. Bowie was suspicious of intermediaries, middlemen, gatekeepers; the internet felt like it might be their comeuppance. To him, record companies were burdensome and suffocating; managers were a waste of everyone’s time and money. Radio wouldn’t play his songs, MTV wouldn’t air his videos. The cognoscenti of the art world seemed to him elitist and a barrier to creativity: Bowie revelled in the chance to hoax them. And of course, for Bowie, the apparatus of organised religion impeded, even corrupted, humankind’s relationship with God. Bypass the church and its dogmas and its priests and you might actually get somewhere.

But something else had been going on. An album had been released and its influence would be profound and nothing for Bowie would be the same again. We have been here before, of course. Except this time, the album wasn’t Bowie’s.

“I naturally fall into melodies,” Bowie had said with some regret while promoting his Outside tour in 1995. “I can’t help but make melodies. I fight that all the time. I’m just good at them. I’m good at writing tunes.”

A first-world songwriting problem indeed.

He continued:

“So, being the kind of obtuse fellow that I am, I fight very hard to go away from that. Otherwise I’d just churn them out. It would be so simple for me to churn out album after album of good tunes, where you walk out of the building singing the set. I don’t have a problem with that. I’m much more interested in doing something with music than creating songs. Songs really don’t interest me that much. They’re kind of singular - they’re just things. I’m much more interested in kind of sitting back and saying ‘yeah, I changed the texture of music in this way or that way - I made music do a different thing’. It’s like vain ideas of changing the course of rivers - I don’t want to build canoes.”

But that was the Bowie of 1995. By 1998, it was time to open the David Bowie Canoe Workshop.

The crackpot experimentation, the playing with form, the subversion of the medium, the wilful antagonism: these would all be left behind, as would the outlandish clobber and hair. Songs, with tunes, and recognisable words and structures, songs that sounded like they were played by a man or a band, recorded in a normal way: these were the future, and would remain so, until the end neared.

We can speculate as to why there was such a change. We could see it as the inevitable next step in a career that ricocheted all over the place; as the product of a man who grew bored quickly with everything, even with pushing boundaries; as a daring turn to stability and order at a time of chaos. We could see it as a continuation of a subtle shift from the improvisational nature of much of 1. Outside to the tighter Earthling. Less charitably, we could see it as the result of seeking greater commercial success, of an effort to keep the Bowie brand at least in some tenuous contact with what passed for the mainstream.

But perhaps there was another spirit at work. Perhaps Bowie had heard something that had shaken him and left him questioning his direction as an artist.

Bowie had long had a curious and complex relationship with Bob Dylan. There were significant differences in style and emphasis: to many onlookers at least, one cherished authenticity, the other celebrated artifice; one focused on the world outside, the other on the world inside; one was deeply rooted, the other deeply rootless; and so on. Dylan was plainly an influence on the folky Bowie of the late 1960s, but seemed to exist in a different universe from, say, the second side of Low. The Bowie track Song for Bob Dylan, from the 1971 album Hunky Dory, is a barbed tribute. After Bowie broke up the Spiders from Mars, Mick Ronson’s next major assignment was as Dylan’s guitarist. Dylan disliked Young Americans but liked “Heroes”. Bowie covered Dylan’s song Maggie’s Farm with Tin Machine and, grislier still, Like a Rolling Stone with Bryan Adams’s band. A curious and complex relationship, like two street cats stalking each other.

Five months after Bowie released Earthling, Dylan released Time Out of Mind, and Bowie was floored. “When I first put his new album on I thought I should just give up,” he said in 1998. Next to Time Out of Mind, much of Earthling sounded ephemeral, even juvenile. For all its charms, Bowie’s album was a skittish affair, a bright thing caught on the breeze; Dylan’s was weighty as a tombstone. Dylan was only six years older than Bowie but sounded inhabited by the centuries, casting his gaze backwards over cities and ruins, drinking with ghosts, interrogating Death, desperate for a glimpse behind the curtain. Bowie was trying to get all the names of the Seven Dwarfs into a song that sounded a bit like The Prodigy.

So pretty much the first song that Bowie recorded in 1998 was from Time Out of Mind. The contrast from the sound of Earthling could hardly be more marked: where so much was once frenetic and processed, now there was something stately and sedate to the point of soporific. The weight of the song, called Tryin’ to Get to Heaven, seems uncomfortable for Bowie, and he sounds like he has no idea how to carry it. The result is deeply unconvincing, and it was not released officially until 2021. But we can think of it as a session in the gym, the sound of Bowie exercising muscles he would need to swim in deeper waters.

David Bowie was good at seeing what was not there. He saw a place where melody could go in r’n’b, funk, house and drum and bass. He saw a place where humanity could go in robotic German music. He saw a place where blues guitar could go in shiny pop. So when he was asked to write music for a video game, he knew what he wanted to contribute: genuine emotion.

The game was called The Nomad Soul (with the prefix Omikron in the US). The player could explore a city; it was hugely ambitious for the time, stretching the existing technology to its limits (and arguably beyond them: there were complaints that it took tiresomely long for its various parts to load). Bowie was a character in the game; he was called Boz. One of his bands were called The Awakened, and the player was mutable and shifting, inhabiting different characters: even here, Bowie’s inclinations towards Gnosticism and Buddhism were apparent. He contributed ten original songs to the game; he wrote them with Reeves Gabrels.

Many of these songs, albeit in different forms, made their way onto Bowie’s next album and the B-sides from its singles. The album was called ‘hours…’ (the lower-case ‘h’, the inverted commas and the ellipsis were deliberate). The only thing radical about it is its difference from Earthling: the change of direction is more jolting than any before, which is perhaps its most notable achievement.

‘hours…’ is an album by a middle-aged man, inhabiting the character of a middle-aged man. At least no one could now accuse him of trying too hard. In most of these songs, this man is quietly rueful, in low mood, made low by his life, by the fact its has proved disappointingly colourless and pedestrian, flames snuffed out, passions dulled. There are flashes of hope, but maybe these only add to the hushed tragedy. Bowie was keen to stress that this man was not him.

‘hours…’ may have the unwanted distinction of being the most forgotten and forgettable album of Bowie’s career. It is never as overtly wretched as the worst moments of Tonight or Never Let Me Down, and it has some moments to savour, not least some of his strongest melodies of the 1990s. But it possesses an almost oppressive mediocrity, exacerbated by its production, which is weirdly clammy and airless and weightless, and for which we have only Bowie and Gabrels to blame. Some tracks sound like demos, plasticky synths playing parts that come across like sketches for acoustic instruments. And ‘hours…’ somehow sounds simultaneously too bright and too murky, like a blurred photograph given a gloss finish; that a few of its tracks were remixed and fleshed out by another producer within weeks of its release rather suggests Bowie felt the same. It peaked at number five in the British charts before melting away; it left no mark. Some reviewers liked it, but most were unimpressed; the typical reaction was boredom. The magazine Select said Bowie was now a “more high-brow Sting”; the NME likened him to Gary Barlow. In terms of public consciousness, ‘hours…’ might as well have never existed.

Bowie’s music was barely even a matter of curiosity by this point; it was hard to see where he might fit. In a stroke of what seems more like desperation than inspiration, he wanted the r’n’b girl group TLC to sing backing vocals on its lead single; Gabrels, eager as ever to save Bowie from himself, once more proved his worth by vetoing the idea.

If ‘hours…’ had a place anywhere, it was in a broader current of British guitar music, which had typically been bright and bold from 1994 to 1997, before losing its energy and turning inwards, as if hungover, as shadows lengthened on the decade. There was a brief and low-key tour of small venues to promote the album; there was something to be said for the intimacy of the shows, but they were rather lacking in spectacle or drama or intensity. It almost felt apologetic.

But ‘hours…’ is no write-off, partly because there are good songs yearning for escape, and partly because there is something important stirring here, among the drift and listlessness. As Bowie reaches for a new way of being Bowie, he reaches too for Christianity. It’s there on the front the album, on the back of the album, within the album.

The cover of ‘hours…’ is inspired by the Pietà, a motif in Christian art from the Renaissance onwards. The classical image depicts the Virgin Mary cradling the body of Christ after the crucifixion. Bowie’s version depicts Bowie cradling the body of Bowie: the former being a fresh-looking, angelic Bowie, sporting Bowie’s new haircut; the latter being an approximation of the Earthling-era Bowie. Something is being laid to rest.

The lyrics of the album are seasoned with Christian terminology: there are hymns, gods, the eternal, the damned. Most intriguingly of all, there are “angels of promise,” a term used for the spiritual beings that convey God’s promises to humans; the best-known is Gabriel, who told Mary that she was pregnant with the son of God. The song in which they appear is the second part of what we might call his ‘angels trilogy’; we will explore this properly in the next piece. The song Seven is spiritual in a broader sense: Bowie described it as a song of ‘nowness’, and he would talk around this time of having learned to take life day by day. Such ideas are customarily associated with Buddhism, but they are present in Christianity too, both in the teachings of Jesus and in disciplines such as the Examen. (Tapping into other traditions, there is an instrumental track that deploys a koto, the Japanese instrument Bowie said he used to evoke a sense of spirituality.)

One the back of the album are a trio of Bowies and a snake. The image evokes classical depictions of the Fall of Man: there is Adam on one side, Eve on the other, one of them in distress; and there is God, and there is the Devil, in the form of a serpent.

Bowie chose the album title for its multiplicity of meanings reflecting its themes, most obviously ‘hours’ and ‘ours’. But it also suggests the ‘books of hours’ popular among Christians in the Middle Ages, marking and hallowing the passage of time with prayer.

And there was a further development, which was quite unexpected, but seems of a piece with all this. For the first time since 1976, Bowie incorporated into his live sets the song Word on a Wing, his desperate hymn of devotion.

We can only speculate as to what was going on for Bowie in a deeper sense at the end of the 1990s. Superficially at least, he seemed entirely content: his manner in interviews was typically upbeat to the point of irrepressibility; he would talk about his joyous marriage, his sense of artistic satisfaction, the pleasure he derived from daily life, his hopes for the new century. But he was aware of shadows in his subconscious. Dreaming is a major theme of ‘hours…’, whose working title was The Dreamers, and dreams would go on to play a major part in his work. As he told Uncut in 1999:

“I suspect that dreams are an integral part of existence, with far more use for us than we’ve made of them, really. I’m quite Jungian about that. The dream state is a strong, active, potent force in our lives.

“That other life, that doppelganger life, is actually a dark thing for me. I don’t find a sense of freedom in dreams; they’re not an escape mechanism. In there, I’m usually, ‘Oh, I gotta get outta this place!’ The darker place. So that’s why I much, much prefer to stay awake.”

The clothes were casual, the attitude jovial; in his dealings with his fans on BowieNet, he usually came across as just another bloke in his early 50s. The edge and angst of his music and performances from even two years ago seemed distant, let alone the torment of the mid-1970s. But dig a little, and those fears and terrors still held power. And as a means of salvation, it seems, so did Christianity.

Something of the old Bowie refused to die. It was the Bowie of the Arts.

His confidence in his own paintings had grown in the early part of the decade, to the point where he felt able to hold his own exhibition. He had become a vocal advocate of many British artists of the time: the landmark 1997 exhibition Sensation, displaying works by the likes of Damien Hirst, Tracey Emin, Sarah Lucas and Marcus Harvey, had been a hit in London but faced difficulties when it moved to New York until Bowie offered financial assistance. He also displayed its art on BowieNet. Bowie was on the editorial board of the magazine Modern Painters, occasionally interviewing the leading artists of the period.

One of his ventures in 1998 was a series of short programmes for the BBC. Each episode was on a particular piece of art, about which a commentator of note would reflect. The focus of one programme was a work by Richard Devereux; it was called In Stillness and In Silence, and comprised a slab of stone on which was inscribed the word SACRED. The commentator on this occasion was Bowie himself.

This is what he said:

The carved word is one of the most complex expressions. Memory made manifest. It’s something that straddles past and future, without ever quite being present. Or rather, it at first seems indifferent to the present. There’s a tension of a most unfathomable nature. The word desires to be understood, to have meaning. But you somehow feel that it’s not you yourself that the word is addressing. It washes over you. Holding a dialogue with something arcane that’s maybe not mortal. And you feel intrigued. Captured, even. You’re aware of a deeper existence. Maybe a temporary reassurance that, indeed, there is no beginning, no end. And all at once, the outward appearance of meaning is transcended. And you find yourself struggling to comprehend a deep and formidable mystery. I am dying. You are dying. Second by second. All is transient. Does it matter? Do I bother? Yes, I do. Life is fantastic. It never ends. It only changes. Flesh to stone to flesh. And round and round. Best keep walking.

And on Bowie walked, into the new millennium. But would his god walk with him?

If you enjoyed reading this piece, I’d be really grateful if you would please share it with others by pressing the button below. Thank you.

Next on Bowie/God:

Thrills and terrors as Bowie confronts God