Sex and the Church

Bowie talks at you at some length about matters of flesh and the spirit. It shouldn't work, but somehow it does

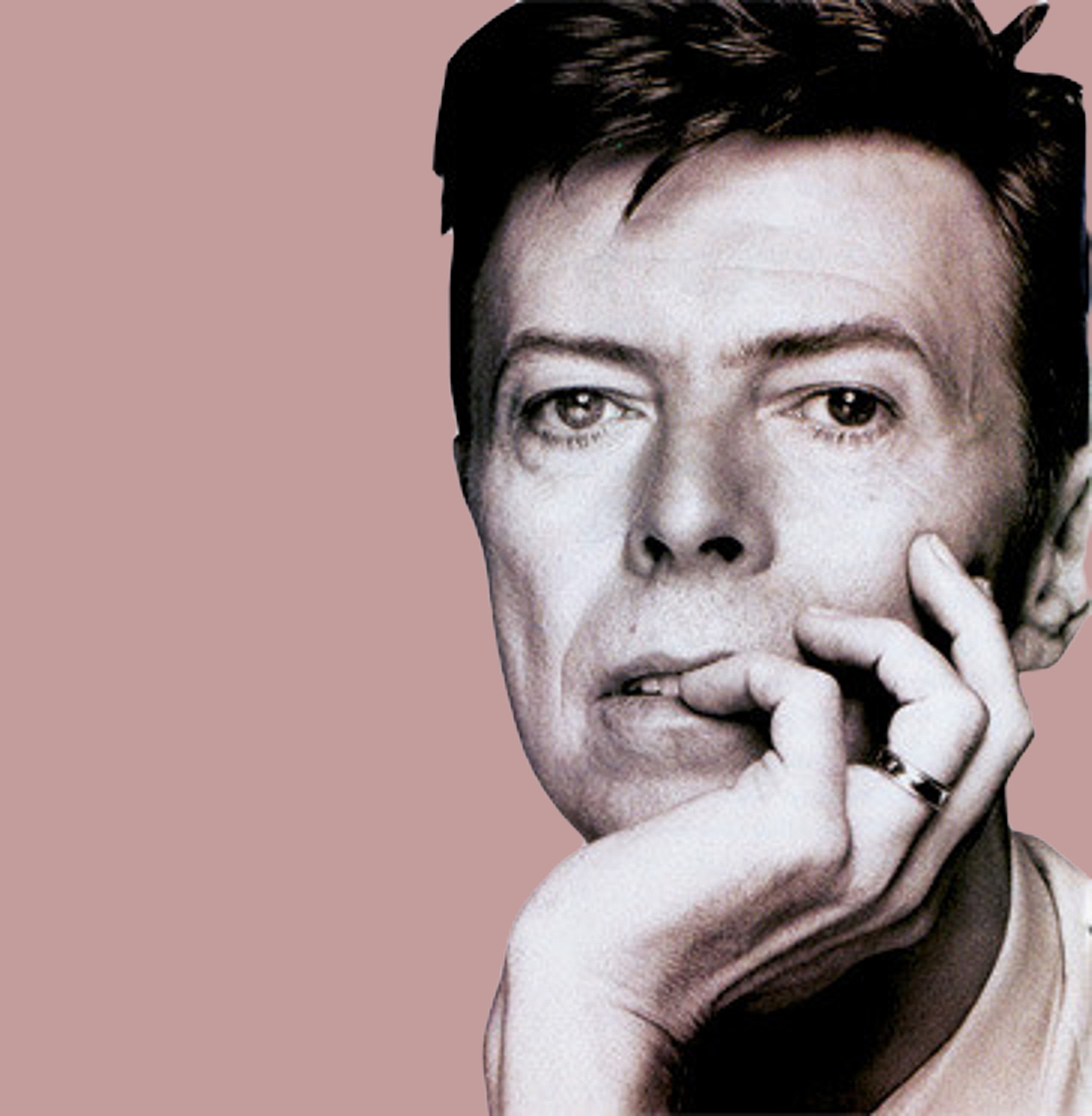

David Bowie, pictured on the back of the album The Buddha of Suburbia, 1993 (colour manipulation by Peter Ormerod)

David Bowie wanted everything.

He wanted Little Richard and Anthony Newley and r’n’b and mime and musical theatre and Jacques Brel and Kabuki and melodies and funk and Europe and America and machines and hearts and black and white and the past and the future and depth and surface and abstract and concrete and the horizon and the ground beneath his feet and left and right and stardom and obscurity and the worldly and the spiritual and analogue and digital and the intellectual and the carnal and soul and blood.

Or as he put it: “I’m a born librarian with a sex drive.”

The problem is that the world demands choices. He said in 1995 that he was very good at making choices. But often, he chose not to choose. This resulted in some of his best work, when creativity exploded in the collision of disparate worlds. But it would drag his work down, too: songs could become cluttered, albums unfocused. A law written into the fabric of existence dictates that if you do something, you cannot do something else. As with any law, there are loopholes, but the principle is pretty solid.

This reality had confronted Bowie in 1967. He was seriously considering dedicating his life to Buddhism and becoming a monk. But that meant abjuring certain worldly pleasures; it also meant shaving off his hair. So he chose music.

Now it was 1993, and he had something to say about all this.

David Bowie’s marriage to Iman in 1992 led to an enduring union. But it also brought about a reunion. Among the guests at the wedding in Florence was Brian Eno, with whom Bowie had not worked since 1979. Their work had diverged wildly in the intervening years, but the two retained a certain affinity: they found themselves discussing music with their familiar enthusiasm, and made tentative plans to collaborate again.

Unlike many of Bowie’s tentative plans, this one would actually come to fruition; but not yet. Top of Bowie’s agenda was Black Tie White Noise, the album he was making with Nile Rodgers. When it came to the project after that, Eno would again be absent physically, but his spirit would infuse it.

The novelist Hanif Kureishi interviewed Bowie in February 1993. It so happened that the BBC was working on an adaptation of Kureishi’s acclaimed novel The Buddha of Suburbia. Kureishi took to the opportunity seek permission to use Bowie’s ‘70s songs, in keeping with the setting of the series. “I thought you were never going to ask,” said Bowie. But Bowie misinterpreted the request: he thought he was being asked to write a new soundtrack. So he did.

The Buddha of Suburbia, loosely autobiographical, had certain parallels with Bowie’s own life. The story was set in Bromley, where he spent most of his childhood, and followed a teenager through mysticism, music and sex. Its title alone mentioned two formative influences on Bowie’s life and work.

Bowie wrote some varied instrumental pieces for the production. He also composed the title track, his most confident and accomplished exercise in traditional songwriting and performance since Absolute Beginners in 1986. Unusually for him, it made direct lyrical and music references to his past. His work for the series was nominated for a Bafta.

But then Bowie did something of pleasing artistic adventure and charming commercial naivety. He went back into the studio with the multi-instrumentalist Erdal Kızılçay and producer David Richards and completely reworked the music. Employing experimental methods he had used with Eno in the 1970s, he made an entirely new album: what started as slight instrumentals became fully-fledged pieces. The resulting record was released in November 1993. It was called The Buddha of Suburbia and was labelled as a soundtrack, despite not being a soundtrack and despite having only a tangential relationship to The Buddha of Suburbia. Bowie’s name appeared on the cover, but was barely noticeable, while his face appeared only on the back. It was a great lost Bowie album from the moment it was released.

To this day, it remains something of a forgotten gem. It is rarely discussed; it is often overlooked. This is a pity, because it means it has never had the audience it deserves, and many who would enjoy it have not heard it; years later, Bowie rated it among his best albums. He was dismayed by its shambolic marketing, but perhaps it belongs in the shadows; perhaps it would be damaged by sunlight. Like Lodger before it, perhaps it is best thought of as one long B-side, and it is none the worse for that.

The first track is the title track. The second is one of the oddest things he recorded. It is called Sex and the Church.

In a sense, there’s little to say about it. It’s all on the surface: nothing is hidden and there is nothing to interpret. It’s just Bowie talking at you about, well, sex and the church. It’s like being cornered at a party by a repetitive man whose confidence far exceeds his knowledge. You get his gist pretty quickly and you’re quite keen to speak with someone else but he just goes on and on. You can’t catch every word so you kind of nod and smile.

“Though the idea of conversion [did he say conversion? maybe he said confession] is said to be the union of and his bride, the Christian, it's all very puzzling.”

Yeah!

“All the great mystic religions put strong emphasis on the redeeming spiritual qualities of sex. Christianity has been pretty muddled about sex”

[did he say muddled or modern?] Mmm.

[is he including Christianity as one of the great mystic religions here, or is he contrasting Christianity with your Buddhism and your Hinduism?]

“I think there is a union between the flesh and the spirit." [how convenient]

[what was that? “All religion is power,” was it? what about those great mystic religions you just spoke so approvingly about? never mind]

“Give me the freedom of spirit and the joys of the flesh”. Ha! Yeah, who doesn’t? [oh, you’re being serious]

[maybe you can stop saying sex and the church now]

And yet. If there was a list titled Bowie Songs That Shouldn’t Work But Somehow Do, this would probably be at the top. There are intriguing things going on here: skippity percussion, churning synths, house beats, sax wails and refrains, sudden snare rolls, Bowie’s speaking voice being electronically doubled and given melody, and a suppleness and subtlety and even a catchiness to the arrangement that, despite everything, gives shape and purpose to what could easily have been six of the most listless minutes of Bowie’s career. Blimey, he’s somehow hypnotised you, the bastard.

It also has to be said he is on to something. In Christianity, the relationship between the flesh and the spirit remains unresolved. And it goes beyond matters of sex.

A prevailing idea in what Christians call the Old Testament (known to Jews as the Hebrew Bible) is that God showers earthly gifts on those who do his will. They are rewarded with military victories, with livestock, with wives, with children. But the writer of Ecclesiastes, one of the many books that comprise the Old Testament, notices that the wicked appear to prosper at least as much as the good. In the New Testament, Jesus subverts the conventional understanding of blessing - “blessed are the poor” and “one’s life does not consist in the abundance of possessions,” he teaches - and, after him, St Paul develops a theology of flesh and spirit that sanctifies hardship, suffering and deprivation. The tension between these positions was a preoccupation of the 19th century intellectual movement known as German Romanticism; as we will see, it was a tradition with which Bowie found great kinship.

Then there is sex itself. Various sexual acts and forms of behaviour that would typically be condemned today are described and portrayed in the Old Testament, often with little moral commentary. The Song of Songs, one of the books of the Old Testament, is an erotic poem; it makes no mention of God, but it is generally interpreted as an allegory telling of God’s love for his people. In the New Testament, the gospels report just one example of Jesus mentioning sex, in the context of a question about divorce; but St Paul was more vocal on the matter, wishing others would follow his example of celibacy while understanding it as a gift from God.

As Christian theology developed over the following centuries, the virginity of Mary, the mother of Jesus, became regarded as a virtue, and Catholic dogma held that Mary herself was conceived “immaculately”, without the taint of sin that they believed was passed on through sex. Catholic priests were forbidden to marry or have sex. Sex for anything other than procreation was outlawed.

The Church of England has tended to take a more moderate view, allowing its priests to marry and have children, and permitting the use of contraception. Today, its stance is that sex is basically good: clergy conducting marriages usually state, often to the embarrassment of all concerned: “The gift of marriage brings husband and wife together in the delight and tenderness of sexual union.”

So Bowie was right. Christianity has been pretty muddled about sex. But it is of course far worse than that, because scandal after scandal after scandal involving sexual abuse have consistently undermined the claim of churches - be they Catholic or Protestant - to any kind of moral leadership. The Church of England agonises interminably about homosexuality, causing immense emotional and spiritual pain to many; meanwhile, the Anglican church in Uganda has supported its government’s draconian anti-gay policies, which include the death penalty for certain acts.

It feels quite crass to bring this back to Bowie, and to a generally inconsequential track on a little-heard album. But there is something telling here. Sex and the Church, restrained as it may be, gives weight to Bowie’s hostility towards organised religion. And it adds colour to a key component of his personal philosophy: binaries are there to be broken. Institutions, and individuals, wield power by a manipulative blend of giving and withholding. Yet Bowie preached that life doesn’t need to be either/or; it can be both-and. As an artist, Bowie was not overtly political, but the art that flowed from this perspective was political in the most profound sense: many have found it revolutionary in their own lives and among their own people. Those loopholes mentioned above? Maybe it’s the job of art to widen them.

Sex and the church. You can forgive him for going on about it.

Next on Bowie/God:

Neo-paganism, mythology and the millennium

A great way of supporting this series to subscribe to it. Each piece will be emailed directly to you as soon as it’s published, so you won’t miss a thing. Subscribing is quick, easy and free. Thank you.

If you enjoyed reading this, I’d be really grateful if you would share it with others by clicking the button below. Thanks!