God is on top of it all

David Bowie offers a prayer to the 'cornerstone of his existence' and causes a sensation. But why?

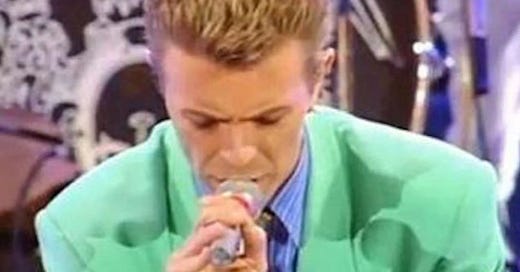

David Bowie at the Freddie Mercury Tribute Concert for AIDS Awareness in 1992

For once, it was all going so well.

David Bowie was back at Wembley, triumphant. He had sung a bravura Under Pressure with Annie Lennox; he had brought Mick Ronson on stage to join him for only the second time in 29 years; he had roused the crowd with a soaring “Heroes”. It was April 1992, and it felt a long way from the shambles of 1987.

Then, in front of 72,000 people in the stadium and hundreds of millions watching on TV, Bowie fell to his knees and prayed:

Our Father, who art in heaven,

Hallowed be thy name.

Thy kingdom come, thy will be done

On earth as it is in heaven.

Give us this day our daily bread,

And forgive us our trespasses,

As we forgive those who trespass against us.

And lead us not into temptation,

But deliver us from evil.

For thine is the kingdom, the power and the glory,

For ever and ever.

Amen.

A lot had happened in those five years, and quite a lot hadn’t happened.

Bowie knew in 1987 that things could not go on as they had been. He felt creatively bankrupt and personally despondent. He seriously contemplated quitting music; he realised he had to quit alcohol. Having been idolised and lionised like few others, he was now an object of scorn and ridicule.

The music press gave him a nickname: The Dame. It stuck, because it was perfect. It carried connotations of preposterous grandness; there was faded aristocracy in there and pantomimic absurdity. There was artifice, preciousness, pomposity, pretentiousness; a brittle, tottering shallowness. And Bowie knew it.

So he tried to disappear.

Bowie’s only public performance in 1988 took place at the Dominion Theatre in London at a benefit concert for the Institute of Contemporary Arts. It was a relatively low-profile affair and the best thing he had done for years. He seemed to know this is where he should be; but, not for the first time, he was helped there by others.

One of those was Reeves Gabrels. Bowie met him via the Glass Spider tour; Gabrels’s then-wife had been its publicist. Gabrels would play a key role in Bowie’s creative revival: first personally, by talking him out of his dejection through directness and humour, and second musically, by turning out to be the guitarist of Bowie’s art-rock dreams, summoning chaos, squall and even, when the occasion demanded it, melody.

And two of those were Louise Lecavalier and Édouard Lock. They had formed the dance troupe La La La Human Steps in their native Canada; it was an avant-dance troupe with a taste for blending elegance with aggression.

At the ICA show, Gabrels played guitar, and Lecavalier and Lock danced with Bowie on stage. The result was thrilling. There is another dimension in which this is the Bowie who saw out the ‘80s and saw in the ‘90s: sharp, sleek, edgy, contemporary, daring, genuinely cool for arguably the first time since 1980.

But that is not the dimension in which we find ourselves, because Bowie and Gabrels ended up forming a band called Tin Machine. Their drummer was Hunt Sales and their bassist was Tony Sales; they had played with Bowie on the Iggy Pop album Lust for Life and its ensuing tour in 1977. They were no-nonsense, old-school, bluesy rockers, and in theory the ideal foil for the more cerebral and arty Bowie and Gabrels.

Tin Machine tend these days to be written out of the official Bowie narrative, and some may question their place in this series. Bowie was at pains - sometimes quite excruciating pains - to assert they were a proper, bona fide band, rather than his personal vanity project. He would always be interviewed and photographed with other members, and they would speak unceasingly of their collaborative and democratic approach to making music. The extent to which they reflected Bowie’s own artistic impulses - and, for our purposes, Bowie’s own spirituality - is therefore debatable.

So we will not dwell on them for long, but there are at least morsels of significance here. An obvious place to start would seem to be a song called Bus Stop, because it concerns a woman who claims to have seen a vision of Jesus, and its chorus goes:

I'm a young man at odds with the Bible

But I don't pretend faith never works

When we're down on our knees

Prayin' at the bus stop

Yet it is a jocular number, the closest Tin Machine ever came to comedy, a vaudeville vignette recalling, of all things, Bowie’s debut album. Best not take it too seriously, then.

But perhaps more revealing are the songs that appear most clearly to emerge from the wilderness in which Bowie felt so lost. There had been something lacking from Bowie for years; now, he was confronting that lack. Sometimes, the result would be fury, as heard on the song Tin Machine:

Raging, raging, raging

Burning in my room

Come on and get a good idea

Come on and get it soon

But sometimes, more interestingly, the result would be numbness and detachment. Tin Machine recorded two genuinely great songs, and they both have this mood.

One is called Goodbye Mr Ed; it is the last song on Tin Machine’s second and final studio album. The other, found on their first album, is more significant and is called I Can’t Read. It is a portrait of spiritual and creative impotence. Backed by a musical thoughtfulness that was unusual for Tin Machine, Bowie sings blankly:

Money goes to money heaven

Bodies go to body hell

I just cough, catch the chase

Switch the channel, watch the police car

The chorus goes:

I can't read shit anymore

I just sit back and ignore

I just can't get it right, can't get it right

I can't read shit, I can't read shit

It also sounds here like Bowie is singing “I can’t reach it anymore,” which would certainly fit with the sense of a man who knows, or fears, he can no longer touch greatness. Given the presence of other puns in this album, we can surmise this is intentional.

This was by some way Bowie’s favourite Tin Machine song: he recorded it again in 1996 and kept it in his live sets for the rest of the decade. He singled it out in interviews following the band’s demise as the one Tin Machine track that should be heard by Tin Machine sceptics (of which, by that point, there were many). Some may see an irony here: a man sings of being unable to reach it and, in doing so, reaches it. But there is a spiritual truth here for those willing to see it.

There is a strong tradition in Christianity at least of facing up to one’s failings and, in doing so, finding salvation. This is what I Can’t Read sounds like. There is almost a sense of ecstatic release when the chorus repeats, its melody suddenly buoyant, before Bowie’s anguished screams of “no” over wails of guitar. It is of a piece with the work of the philosopher and theologian Peter Rollins, which embraces doubt, complexity, unknowing and brokenness, pointing to Christ’s cry of abandonment on the cross - “My God, my God, why have you forsaken me?” - as foundational to Christian spirituality.

This is obviously not to equate the two, but it is surely telling that this is the moment when Bowie starts to find himself on record again. There would still be mess and mediocrity to come, but I Can’t Read is the point where his story turns.

There is context to Bowie’s prayer.

The full name of the event at Wembley was The Freddie Mercury Tribute Concert for AIDS Awareness. Mercury, with whom Bowie had duetted on Under Pressure in 1981, had died in November 1991 from an Aids-related illness.

Seven years earlier at Live Aid, Bowie broke the celebratory atmosphere: after saying “let us not forget why we are here”, he cut short his set to play a film showing distressing scenes from the Ethiopian famine. Here, coming out of “Heroes”, Bowie again returned to the purpose of the concert, paying tribute to those “that have been toppled by this relentless disease”. Looking straight at the camera, he continued: “I’d particularly like to extend my wishes to friend Craig - I know you’re watching, Craig - and I’d like to offer something in a very simple fashion that’s the most direct way that I can think of doing it.”

David Bowie was lonely in 1990. His hairdresser noticed, and invited him to a party. His hairdresser also invited Iman Abdulmajid, a supermodel. “My attraction to her was immediate and all-encompassing," Bowie said. “That she would be my wife, in my head, was a done deal. I'd never gone after anything in my life with such passion… I just knew she was the one."

Iman was and remains a committed Muslim. She married Bowie - to whom she has always referred as David Jones - in a private civil ceremony in Switzerland two days after the Wembley concert in April 1992. They held a religious wedding a few weeks later in Florence, at St James’s, an Anglican church known locally as “the American church”. As Bowie put it at the time to Hello! magazine: “We did all the bureaucracy and all the paper signing but we didn't really feel married. I know the forms were signed, but at the back of our minds our real marriage, sanctified by God, had to happen in a church in Florence.”

Bowie’s lifelong friend, fellow traveller and sometime musical collaborator Geoff MacCormack sang with the young David Jones in the local church choir when they were children. At the wedding, MacCormack read Psalm 121:

I will lift up mine eyes unto the hills; from whence cometh my help?

My help cometh from the Lord, which made heaven and earth.

He will not suffer thy foot to be moved: he that keepeth thee will not slumber.

Behold, he that keepeth Israel shall neither slumber nor sleep.

The Lord is thy keeper: the Lord is thy shade upon thy right hand.

The sun shall not smite thee by day, nor the moon by night.

The Lord shall preserve thee from all evil: he shall preserve thy soul.

The Lord shall preserve thy going out and thy coming in from this time forth, and even for evermore.

Thereafter, Bowie would always prize family life above all else.

The prayer drew quite a reaction.

First there was the crowd. When it realised what was happening, it fell into a deep silence, save the odd yelp of encouragement; the moment was met with reverence and respect.

Then there was the media. The prayer dominated the coverage of the concert. The response was predominantly one of surprise: “It was one of the most unexpected gestures of the evening,” began a piece that ran in newspapers across the UK. Elsewhere, there were cringes: “By common consent at least in the Whitstable Times office the most embarrassing moment in the otherwise magnificent televised concert tribute to Freddie Mercury on Monday was when David Bowie got down on hands and knees to say the Lord’s Prayer.” The Daily Mirror ran an opinion piece headlined “The danger in Bowie’s prayer”, arguing that the “cosy, glossy, star-filled hype of the concert” obscured the harrowing reality of Aids. Readers had their say, too: the Irish newspaper The Sunday World published a letter from a Mr P Ryan of Dublin, who wrote:

“I felt absolutely embarrassed when I beheld David Bowie dropping to his knees at the Wembley AIDS gig and reciting the Lord’s Prayer. Why do these stars have to use religion as part of their act? When was David Bowie last inside a church? I haven’t felt so disgusted since Sinead O’Connor’s horrendous rendering of ‘Silent Night’.”

Mr Ryan could be forgiven for not knowing this, but David Bowie was just getting about as godly as a British rock star ever would.

“God plays a very important part in my life. I look to him a lot and he is the cornerstone of my existence - even more as I get older.”

So said Bowie the day after his wedding in Florence. “But it is a one-to-one relationship with God. I believe man develops a relationship with his own God.”

Bowie reflected on the Lord’s Prayer episode in an interview with Tony Parsons for the magazine Arena the following year:

I decided to do it about five minutes before I went on stage. Coco [Schwab, Bowie’s long-term personal assistant] and I had a friend called Craig who was dying of AIDS. He was just dropping into a coma that day. And just before I went on stage something just told me to say the Lord’s Prayer. The great irony is that he died two days after the show.

In rock music, especially in the performance arena, there is no room for prayer, but I think that so many of the songs people write are prayers. A lot of my songs seem to be prayers for unity within myself. On a personal level, I have an undying belief in God’s existence. For me it is unquestionable.

Looking at what I have done in my life, in retrospect so much of what I thought was adventurism was searching for my tenuous connection with God.

This, from a man who had appeared so dismissive of prayer nine years earlier; but who had also sung of kneeling and offering prayer in the desperation of the mid-1970s.

He was also open about what he believed were the spiritual forces at work during those dark days:

I was always investigating, always looking into why religions worked and what it was people found in them. And I was always fluctuating from one set of beliefs to another until a very low point in the mid-Seventies where I developed a fascination with black magic.

And although I’m sure there was a satanic lead pulling me towards it, it wasn’t a search for evil. It was in the hope that the signs might lead me somewhere. There seemed to be a path inherent in kabbalistic religion. There seemed to be a path that one could follow. And of course it helped greatly that it was all so drug-induced. That really helped to blur the sense of reality of what I was getting involved in.I felt totally, absolutely alone. And I probably was alone because I pretty much had abandoned God.

He seemed determined never to repeat the mistake.

Amid all this, David Bowie was becoming David Bowie again.

Tin Machine had released two studio albums, to diminishing interest. Between them, in 1990, Bowie went on a solo world tour: the premise was that he would sing all his famous songs, but for the last time. The public helped choose the setlist via telephone voting. The resulting tour, named Sound+Vision, succeeded only partially. It looked good, a world away from the clutter of the Glass Spider shows: it pioneered the use of large-scale projection, a seemingly ubiquitous feature of performance today, with stark lighting and Bowie looking like a slightly more flamboyant version of the Thin White Duke (the Thin White Dandy, perhaps). But it sounded weak, Bowie’s small band often fatally underpowered. Bowie’s mood worsened, too: he grew chippy in interviews and his voice struggled, leading to an uncharacteristic display of frustration.

The second Tin Machine tour ran from October 1991 to February 1992 and was troubled in its own ways. The band were by then well aware of their detractors, and affected to face the opprobrium with defiance: it was called the It’s My Life tour and the band wore t-shirts bearing the words ‘Fuck you, I’m in Tin Machine’. If Bowie had been in danger of becoming another stadium-filling crowdpleaser a few years earlier, now he and his band seemed intent on antagonism and confrontation, playing intense gigs in small and sweaty venues. The outcome was understandably divisive, doubtless to the band’s relish; but it was the release of a live album that would finish them. It laboured under the dreadful name Oy Vey, Baby - a calamitously misguided attempted play on Achtung Baby, the title of U2’s album from 1991 - and failed even to chart, a fate that had never befallen any Bowie album. Melody Maker said: “This is the moment where finally, categorically and, let’s face it, lumpily, he ceases to exist as an artist of any worth whatsoever.” There were strong rumours of hard drug use by Hunt Sales, too: speaking years later, Bowie said only that “personal problems within the band became the reason for its demise. It’s not for me to talk about them, but it became physically impossible for us to carry on”.

It is fair to say though that Bowie’s return as a solo artist was hardly reluctant. This much we can infer by his swift choice of new collaborator: it was Nile Rodgers, who had proved so instrumental in crafting the hits that made Bowie the Bowie that Tin Machine was supposed to have destroyed. The first result of their reunion was a relatively low-key release, the snappy but inessential title song from the film Real Cool World; it barely troubled the charts upon its release in August 1992. But as it became clear that nothing could save Tin Machine, Bowie and Rodgers continued working, and the result would be Bowie’s comeback album.

In 1993, the tides of culture were turning, in the UK at least. And something unexpected happened: Bowie became cool again. Attempting to trace paths of cause and effect can lead to simplistic and misleading analysis, but a new generation of British bands was citing Bowie as an inspiration. Foremost among them were Suede; they were proclaimed widely as saviours of British guitar music, and barely a paragraph could be written about them without referring to their love of Bowie. It forced something of a rehabilitation for the long-derided fortysomething: the NME, which had been among his more biting critics, now put him on the front cover with Suede’s frontman, Brett Anderson. Bowie later likened it to “passing on the baton”.

Suede’s self-titled debut album was released on March 29, 1993 and went straight to number 1. Bowie’s comeback album was released the following week and went straight to number 1, thus dislodging Suede: it seemed irony was back, too. In truth, despite the fresh confidence with which Bowie demonstrated and discussed his faith, there is little explicit evidence of it on the record; but there are still aspects that bear examination.

The album was called Black Tie White Noise. Bowie had long been concerned about relations between races; his criticism of MTV in 1983 for playing too few videos by black artists has become one of his most celebrated moments. A week after their official marriage, Bowie and Iman flew to Los Angeles; that night, riots erupted. The spark had been the acquittal of four white police officers who had been accused of brutally beating a black man. “The one thing that sprang into our minds was that it felt more like a prison riot than anything else,” said Bowie later. “It felt as if innocent inmates of some vast prison were trying to break out, break free from their bonds.”

Sadly, the resulting song, which is the title track of the album, is rather muddled in tone and execution. And there is a certain flabbiness to much of the record: it was the first true Bowie album of the 74-minute CD age, and it feels like it. But two standout tracks recall Bowie’s focus and discipline: Jump They Say, a jerky, nervy, yet brilliantly polished hit single, aided by one his best videos; and Pallas Athena. Just as the 1970s Bowie sought to bring a conventionally European melodic sensibility to r’n’b, the 1990s Bowie was striving to do the same with house music. The result was one of his most effective tracks of the decade.

The music starts off sleek and crisp, becoming hypnotic and mysterious and maybe even menacing: relentless beats, minor-key synths, smoky trumpets, eerily layered vocals. The lyrics are few but weighty. Bowie, sounding like a Pentecostal preacher, repeats:

God

Is on top of it all

That’s all

He is later joined by massed voices chanting beneath him, over and over again, “we are we are”, punctuated with a bellow of “praying”.

Pallas Athena takes its name from the Greek goddess of wisdom and warfare; it is not a gushing profession of faith, and the God in question could just as well be an object of fear as love or hope. But in the context of Bowie’s pronouncements around that time, the words seem significant. What they mean is of course open to speculation, but they are in keeping with an offshoot of Christianity known as Gnosticism. And as we will see, Bowie and Gnosticism would share something of a dalliance as the 1990s unfolded.

Short indeed is the list of white pop stars who would lead a conventional prayer at a huge concert: it is one of few places where David Bowie might be in close proximity to Cliff Richard. It remains a curious fact of popular culture that expressions of faith are accepted far more widely from artists who are not white, in the UK at least: Stormzy led a vast crowd in worship at Glastonbury and eyebrows remained unraised. It is worth reflecting on the fact that Bowie’s prayer still feels somewhat jarring.

Why is that?

What might that say about our attitudes towards people of different colour?

Rock’n’roll was built on rebellion; by what point had it enforced its own rules of conformity?

Political statements aside, what is the most radical act an established rock icon could perform today?

“He didn't do that in rehearsal,” said Brian May.

If you enjoyed reading this, I’d be really grateful if you would please share it with others by clicking the button below. Thank you.

Next on Bowie/God:

David Bowie, sex, and the church.