Draw the blinds on yesterday

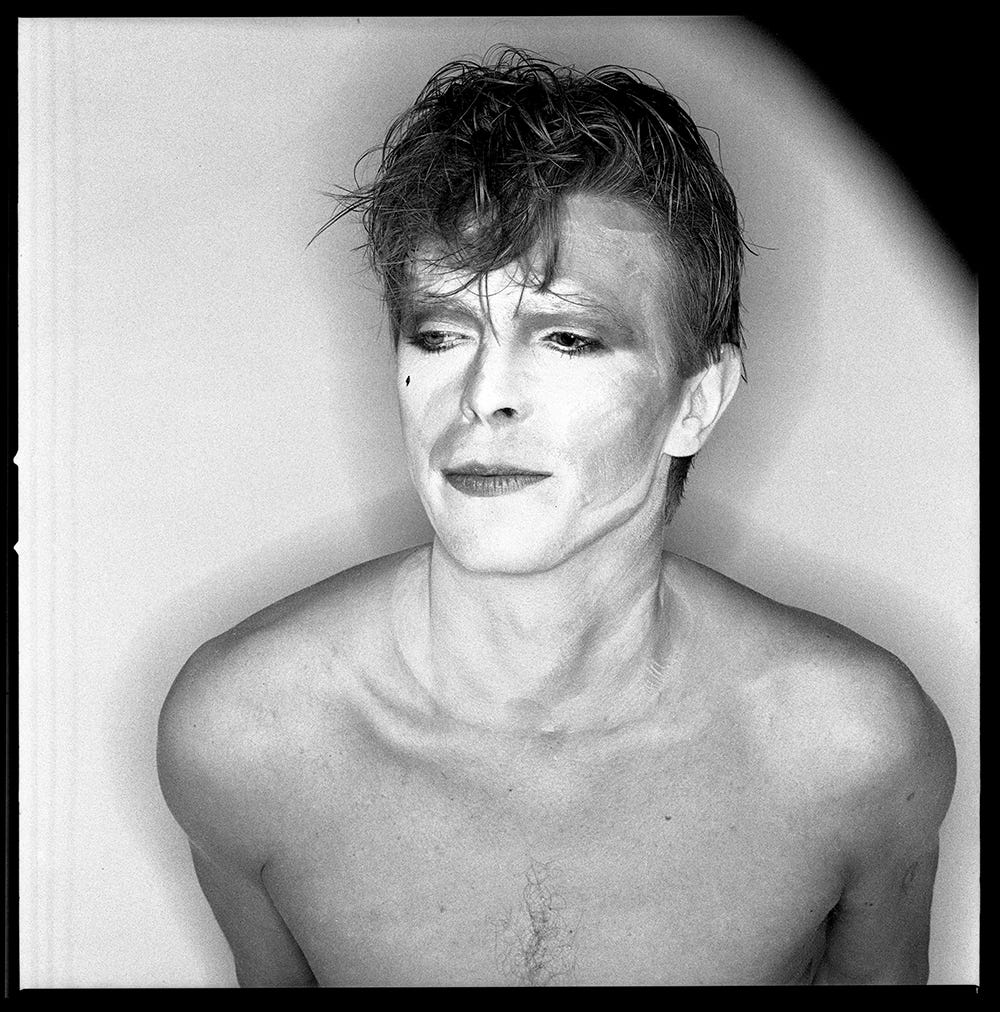

David Bowie wraps up the 1960s and 1970s. What will be left of him in the 1980s?

David Bowie, photographed by Chris Duffy, 1980

It’s as if he thought it would be his last album. In a way, it kind of was. Scary Monsters (and Super Creeps) was released in 1980 and is a remarkable work that grows more remarkable the more one knows about it. To let daylight in upon magic is usually to break the spell. Here, it just illuminates the magic.

What has become apparent only in the decades since it came out - indeed, our understanding of it was deepened just months ago - is just how much the songs draw from his earlier work. But these are not straightforward rehashes of hits, or retreads of proven formulae. Rather, the LP borrows from outtakes, obscurities and curios. Sometimes these old recordings lend some seasoning to new material; sometimes the new material does little more than repackage these old recordings. It is a clearing out of the back of the cupboard, a sweep along the skirting boards; sometimes, he takes what he finds and does alchemy with it.

David Bowie did not mention this at the time; after all, in the public imagination, he was about the New. We know what we now know only because recordings once locked away have since come to light; they have circulated for while via bootlegs, and have more recently been made available through official channels. The relevance of the record to Bowie’s spirituality is therefore not immediately clear; but it becomes more apparent when Scary Monsters (and Super Creeps) is considered not as a retread, but as a recapitulation.

The album has ten tracks.

The first is called It’s No Game (No.1). It is based on a song he wrote in 1970, called Tired Of My Life, which was never properly recorded.

The third is called Scary Monsters (and Super Creeps). That bass riff may sound familiar to those acquainted with Bowie’s oddities; it also appears on The Laughing Gnome, which he recorded in 1967. (Speed of Life, released in 1977, employs it too.)

The fourth is called Ashes to Ashes. It is based on a song he wrote around 1971, called King of the City, which was never properly recorded. Few seemed aware of its existence until 2022, when it was published as part of a reissue of the album Hunky Dory. We will examine Ashes to Ashes more closely in due course.

The fifth is called Fashion. There is a repeated vocal hook which goes “beep beep”. This hook was originally written for Rupert the Riley, recorded in 1971 and never officially released.

The seventh is called Scream Like a Baby. It is a reworking of a song called I am a Laser, which Bowie wrote in 1973 for a group called The Astronettes. It was not released until 1995.

The tenth is called It's No Game (No. 2). It is another version of the first track; in fact, it was recorded before the first track.

That leaves four other songs.

One is a cover version of a song called Kingdom Come by Tom Verlaine, best known as the frontman of the band Television. The song mentions the practice of breaking rocks, also alluded to in both versions of It’s No Game and previously in Tired Of My Life.

Another is called Because You’re Young. The song deals with the passing of time and the sometimes tiresome naivety of youth, as viewed by a man who is no longer young.

Another is called Teenage Wildlife. The song deals with the passing of time and the sometimes tiresome naivety of youth, as viewed by a man who is no longer young.

And the other is called Up the Hill Backwards, whose title happens to serve as a neat description of Bowie’s artistic travels and travails to this point.

The artwork for the album tells the story too. Bowie is pictured on the cover dressed as a Pierrot figure; he had performed in 1967 in the mime piece Pierrot in Turquoise. The covers of his three most recent LPs - Low, “Heroes” and Lodger - are presented in whitewashed form, an example of a kind of auto-iconoclasm that would emerge again much later in his career.

Bowie also appears as a Pierrot in the video for Ashes to Ashes. It ends with the Pierrot walking alongside an elderly-looking woman; an almost identical image appears on the back of Bowie’s 1969 album. The defining song on that album is Space Oddity; Ashes to Ashes is its sequel.

We have already written at length about Space Oddity and its spiritual significance. Bowie’s desire to revisit it might seem surprising in isolation; after all, in the popular imagination, he was always facing forward. But in the context we have established, it feels entirely natural, even inevitable.

Countless analyses have been written of the song. Its depth is as good as unfathomable, which is a remarkable thing to say about a lyric that could be read as almost shallow. Major Tom, the enigmatic figure hurled into space 11 years earlier, is still out there somewhere, and has become addicted to an opiate-like drug. That’s essentially it. But there is an infinite richness here, born of sublime pathos, words soaring above and flowing through and submerged by music of rare subtlety and sophistication, to which you can nevertheless sing along. There are layers of vocals that even now remain a mystery.

So many possible readings are invited. Ashes to Ashes is the death of a dream. Ashes to Ashes is the Fall of Man. Major Tom drifts ever further into the void, having escaped physical gravity; but he is also The Man Who Fell to Earth, brought low by the vanity of mortals. He is Icarus, he is hubris; he is also literally an outcast, a victim, one to whom terrible things have been done. He is Apollo 12, he is the sequel no one asked for but everyone got anyway, he is what becomes of a forgotten infatuation. The last words said to him on earth were “may God’s love be with you”. That love has turned out to be something worse even than hate: it has turned out to be indifference.

Ashes to Ashes makes no mention of God and is not an overtly spiritual work. But it is profoundly existential, and its currency is the folly of humanity. In this, it shares much with religious belief. Indeed, the story is given the trappings of religiosity: its name, and the first line of its chorus, comes from the burial service found in the Book of Common Prayer. The song’s video now feels inseparable from it: “There’s something very religious about the four characters up the front,” said Bowie.

Scary Monsters (and Super Creeps) is the album to which every subsequent Bowie record would be compared. It has a sense of completion, a sense reinforced by its structure: it begins with the sound of recording tape being loaded up and ends with the sound of the tape rattling as it expires.

And so Bowie took all he had done and put it in a box or a parcel or a coffin.

Ashes to Ashes is the funeral.

Ashes to Ashes is not the end.

The profound significance of Major Tom would be confirmed 36 years later. He would be attended by ritual wild and eerie, part of a tableau populated by a false prophet, by a blind seer. All this is to come.

The first song on his next album would sound like something by a different artist, a clean and shiny man. Yet some things are hard to kick.

I never wave bye-bye, he sings.

But I try.

I try.

If you enjoyed reading this, I would be grateful if you would please share it with others by clicking below. Thank you.

Next on Bowie/God:

David Bowie gets the world dancing to songs of God and man